Veer Savarkar - Reflections of a Traditionalist Conservative

Veer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, a figure of 20th century India, evokes strong emotions from all the sides of the ideological spectrum and remains perhaps the most scrutinised Indian politician/freedom fighter of his times. This post is not meant to rebut the allegations made against him by the Nehruvians or the Communists-those tasks have been adeptly handled by Vikram Sampath in his two-part biography, articles and talks. Instead, this blog is about what Savarkar represents to a 21-year-old aspiring Traditionalist Conservative from Savarkar's home state. (I don’t wish to discuss his views on political Islam as there appears to be a consensus within the ‘non-left’ that he was right about political Islam)

To understand Savarkar the ideologue even a little, one needs to at least read Essentials of Hindutva. These essentials. which set the criteria for the question who is a Hindu, were - a common nation (rashtra), a common race (jati) and a common civilization (Sanskriti). All of this is encapsulated in the Sanskrit couplet Asindhu Sindhu Paryanta yashya Bharat Bhoomika, Pitribhu Punya Bhuschaiva Sa vai Hindu Riti Smritah. Savarkar perhaps anticipated the allegations that his Hindutva would be called territorial. Hence, in the same booklet he has went ahead and said that the frontiers of Hindutva are the entire geography of this earth. So even if Hindus settled outside the frontiers of Bharat, they won’t stop being Hindus. Some might ask, what then of the foreigner who wished to become Hindu? Will they fit in the criteria of Savarkar’s? Again, Savarkar anticipated this question and in the booklet said that foreigners can become Hindu if they converted to a religion originating in Bharat; albeit as exception as these foreigners had a different Pitrubhumi. To encapsulate Savarkar's vision, Hindutva is both a deeply rooted cultural identity and a dynamic, inclusive philosophy that extends beyond territorial boundaries while maintaining a connection to its spiritual and civilizational origins.

Other aspects of Savarkar the ideologue are his contentious views on caste, rituals and cow. These views go completely against the beliefs held by a traditionalist conservative. One must understand that Savarkar was utilitarian in his outlook when it came to religion. The epistemological framework that he followed was more in sync with Modern thinkers than with religious scholars. Hence, unlike a traditionalist, Savarkar was ready to question and criticise our scriptures. That was the flavour of those times when the beliefs of our religion were being systemically attacked by British scholars. Due to the political realities of those times with threats & attacks from European & Middle Eastern colonialities, uniting Hindu society was an important imperative. Whichever tradition and structure Savarkar found as an impediment in strengthening Hindu society, he attacked it or questioned its legitimacy since he didn’t view any structure or tradition as divine.

Caste was one such structure. The social separation of different castes, Savarkar believed, over time had created instances of rivalry and oppression. The lack of inter-dining and inter-caste marriages were seen as symptoms of this separation. The way to end the rivalry and unite Hindus was by ending this social separation. Hence, he came to the conclusion that inter-dining and inter-caste marriages was an excellent way to create goodwill amongst communities and forge a social unity which in turn would translate into political unity. This unity, in the end, would ultimately end the structure of caste. With this in mind, Savarkar wrote a collection of essays over time attacking caste.

Caveat - Savarkar didn’t see caste as a negative structure throughout history. He felt that caste was a ‘net positive’ in the past. Savarkar also didn’t blame solely the Brahman community as is usually done by Hindu Modernists and Secularists. But in contemporary times, caste had become a net negative according to him and hence needed to be uprooted.

The view of uprooting caste and promotion of inter-caste marriage goes against the traditionalist-conservative held belief. Hence, while a traditionalist can appreciate the end that Savarkar was working for which was Hindu unity, the means were disagreeable. As someone who epistemologically accepts the authority of Shruti-Smriti-Purana-Itihasa & ontologically believes in their divinity, a traditionalist cannot come to view caste identity as expendable. But that doesn’t mean one doesn’t appreciate the efforts of Savarkar in the temple-entry movement and establishing of Patit Pavan Mandir. It’s a tragedy that the Ambedkarites don’t recognise the efforts of Savarkar in Ratnagiri only due to the Brahman identity of Savarkar. So much for their ‘anti-caste’ ideal.

Similarly, due to difference in the Epistemology-Ontology between an average traditionalist and Savarkar(ite), a traditionalist can never agree with Savarkar’s disbelief in the divinity of the cow or his disbelief in the effectiveness and spiritual/metaphysical aspects of rituals like Śrāddha. But he was a man of his times. Ritualism, worshipping of seemingly lesser beings like the cow, hereditary caste which was seen as akin to class system went against the ideals of egalitarianism and rationality. But Savarkar, unlike a secularist, didn’t hesitate to point out the flaws in Buddhism, Sikhism, Islam, Christianity using the same ideals as the benchmark.

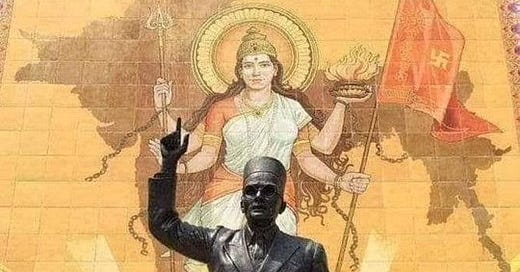

Some might believe after reading the above paragraphs that Savarkar was an atheist. He wasn’t. But the God Savarkar believed in was different than a conventional image/belief of God a Hindu mind has. Savarkar didn’t believe that God moved things. Savarkar didn’t believe in the theory of karma or reincarnation. But multiple times, in his book My Transportation for Life, Savarkar wrote how he prayed to God, speculated that he was at Andaman due to God’s will. If one were to go through his writings, one might conclude that Savarkar was going through his own exploration of divinity and what it meant to him. Hence, one finds some contradictions and paradoxes in his writings on the theme of God. That’s why it’s difficult to place Savarkar in any of the Hindu Darshanas. But he was heavily influenced by Yoga. In his days of incarceration, Savarkar recited the verses in the Yoga Sutras. Another proof of this influence is that he wished to see the kundalini and kripan on the bhagwa flag as the national flag of India. Kundalini, he believed, was the ‘Muladhar’ Shakti of man’s highest progress and eternally blissful state of super consciousness.

In conclusion, Veer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar stands as a unique and complex thinker whose contributions to the freedom struggle and the ideological framework of Hindutva are unparalleled. As a traditionalist, I acknowledge and respect his immense efforts to unite and uplift Hindu society, even if some of his views diverged from traditionally held beliefs. Savarkar's pragmatic approach to social reform and his visionary ideas about Hindu identity continue to inspire, yet they also invite critical engagement and nuanced understanding.

May Tatyarao's spirit inspire us to strive for a strong, united, and enlightened Bharat, and may he take rebirth in his motherland to serve her once again.