India is the motherland of many prominent religions, languages and traditions. India is unique, as it always was, in the richness of its native diversity, which is as diverse as a vibrant rainbow.

But the rainbow is created from a unity, and turns into a unity later on - the seven colours fuse to form the vivacious white. Similarly, India's diversity, especially religious diversity - is largely originated from a single source - Hinduism, or Sanatana Dharma. Many religious streams, like Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, originate from this primeval source.

The history of one among them, Sikhism, is highly intertwined with two religions - the selfsame native Hinduism, and also, Islam, which has had a significant presence in India from the times of Mohammad of Ghor.

In our journey of examining the inspiring and surprising story of the rise and fall of the Sikhs until the advent of British dominance; we shall, in this series, take a deep dive into the history of the faith, its leaders, and its relationship with the contemporary religions of its time - Islam and Hinduism.

This dive shall not at all be exhaustive, but very limited and specific - a few arguments and a certain and particular viewpoint and perspective is humbly intended to be expressed.

The Sikh trajectory can be traced in four distinct phases:

1. The Sikh Gurus

2. The Faith

3. The Crisis and the Sikh Empire

4. The Fall of the Empire

We shall take a keen look at each of these, one by one. Our specific areas of interest would be, as already delineated, its relationship with the contemporary faiths of its time.

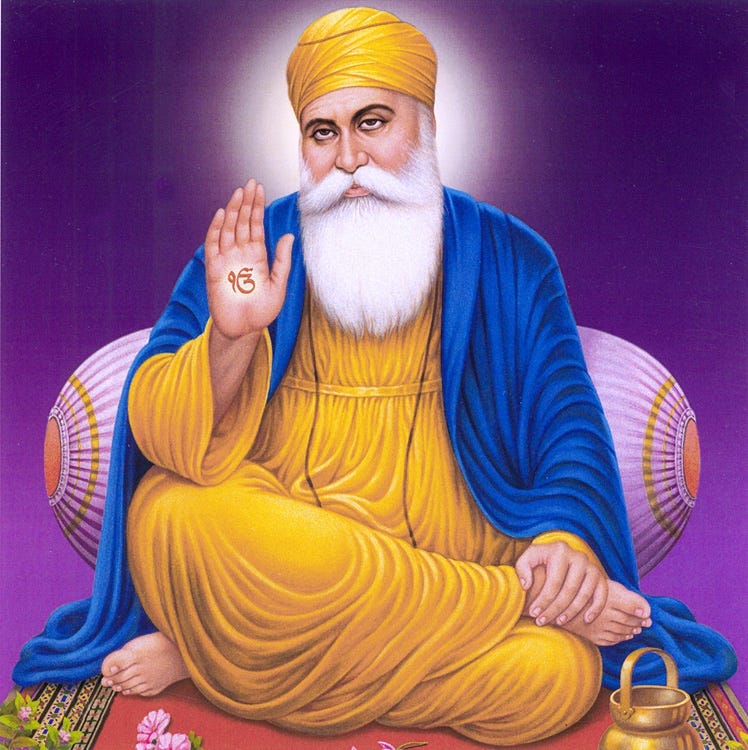

The First Guru - Nanak

The first Guru, the great Nanak, was born in 1469, and was a spiritually thirsty soul, in the manner of the usual trend of the Hindu saints. Inquisitive and pensive from a tender age, he was also rebellious, for he declined to wear the sacred thread.

Now, this certainly marks him different from the Hindus, yes? Or does it not?

One can note that this was done by a little young boy, and, moreover, that this is not something which is completely central to the practice of Hinduism.

The Lingayats or Vira-Shaivas, for instance, who are completely Hindu, do not wear the sacred thread. [1] They are heterodox, but within the fold.

Fairly, it be conceded that many of Nanak's and subsequent gurus' beliefs were in some aspects unusual from an orthodox Hindu standpoint, but not from a heterodox one.

To move forward; Nanak, in search of the religious truth, left his home and wandered in many lands, including Arabia and Persia.

Of when Nanak was at Mecca, an interesting tale clarifies to us in a definite manner, if Sikhism is monotheistic. At Mecca, a Qazi scolded him for sleeping with his feet towards the Kaaba, and then Nanak retorted, in a very Hindu and pantheistic manner - to paraphrase - that God existed in every direction. [2]

Pantheistic tendencies are well-found in Hinduism, and abound in the eternal Rigveda itself; but not in Islam (which is monotheistic), for instance, because a pantheistic viewpoint rejects the notion of a completely separate creator and creation.

Returning from his travels, Nanak proposed several new religious ideas, which, supposedly, set his faith apart from Hinduism.

What were these?

That,

1. Asceticism is not the way to salvation

2. All humans are spiritually equal

3. Idolatry is erroneous

4. Brotherly love

5. Chanting of God's name

Now, are any of these ideas strictly opposed to Hindu views? Let us see.

The prime scripture of Hinduism, as is well-known, the divine Bhagavad Gita, itself gives out multiple paths to salvation, where the jnana marga is only one of them.

Similarly, the Gita is emphatic in asserting that that all beings are spiritually equal [3] -

The wise look upon a Brâhmaña possessed of learning and humility, on a cow, an elephant, a dog, and a Shwapâka, as alike.

About idolatry, if we see clearly, it is clear that according to Hinduism, idols are only a medium of guiding and channeling an individual's bhakti towards Ishvara, and the idol itself is not the object of worship. Hence, Hinduism is not idolatrous. Moreover, if idolatry means the use of sacred symbols in worship; the sacred Sikh Adi-Granth is itself a sacred symbol, and so, Sikhism itself is idolatrous, and one with Hinduism in this regard.

Nanak's followers were called Sikh, a word which comes from the Sanskrit word Shiksha.

Nanak himself was influenced by his reading on many saints who came before him. It is not difficult to estimate that most of them were Hindu saints. Moreover, Nanak, just like his contemporary in Europe - Martin Luther - did not preach any new religion, but contended that religion had become impure in form. [4]

As his successor, Nanak appointed not one of his two sons, but one of his disciples. Nanak somehow managed to avoid the hereditary basis, but very soon, from the fifth guru onwards — from the time of the great Guru Arjun — the guruship did become hereditary. This is not especially a thing to be condemned or praised; but surely, to be noted and observed.

Nanak breathed his last in 1538. But before we conclude our discussion on Nanak, it would be prudent to remember his significant interaction with political Islam.

It would be fair to say that Islamic persecution of the Sikhs, which would take very extreme forms in the future, as we would note as we tread further in the series, starts with Babur's persecution of the first guru - Guru Nanak.

As the influence of Nanak as a preacher began to grow far and wide as generally do the wise words of great men; because his teachings were opposed, in a few aspects at the very least, to Islam, Mughal officials complained to the emperor that Nanak was preaching tenets blasphemous to accepted religion. This had a great effect, for Nanak then remained imprisoned in the Mughal prison for seven whole months. This was the first Sikh political encounter with Islam, whose relationship with the Sikhs remained, to a huge extent, one of conflict and not of amity. After the months had passed, Nanak was released after he eloquently defended his doctrine before Babur, and was let free. [5]

And thus concludes the first part of the series. In the subsequent parts, we would explore the later gurus, as we would sail in this sea, desirous of reaching the shores after the journey has borne the intended fruits.

Footnotes

1. Outline of Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Dr RC Majumdar (1927), p. 508.

2. The Sikhs, Sir John JH Gordon, (William Blackwood and Sons, 1904) p. 15.

3. Bhagavad Gita, verse 5.18.

4. The Sikhs, Sir John JH Gordon (William Blackwood and Sons, 1904), p. 18.

5. ibid, p. 23.

Appreciate the writing ✍️ but I think you all should go in more detail about the events

“About idolatry, if we see clearly, it is clear that according to Hinduism, idols are only a medium of guiding and channeling an individual's bhakti towards Ishvara, and the idol itself is not the object of worship.” Yet Muslims and Sikhs alike still see it as idolatrous.

Hindus are still a polytheistic people with reverence to multiple natural aspects despite believing in the ever panentheistic world-soul.

Sikhs of course get their anti-idolatry influence from Islam, not Hinduism. The question of idolatry in Hinduism was never a question to begin with. Idols were never anything bad. The shame about idols only ever developed with the predominance of Islam.

Theres no point in Hindus trying to appeal to Sikhism. Its a religion with half Islamic influences anyways. Its still a break from our ancient past and philosophies of Vedanta, not a reformation of it. Sikhism is no different than Arya Samaj, influenced by its shame about idolatry in the face of Abrahamic colonizers. That isn’t a reformation of Hinduism back to its original roots, its a perversion of it to be more fitting to colonizers.