The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.

- Karl Marx

This is the ominous sentence which marks the inauguration of the Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx. [1] Class struggle, class warfare, class conflicts - they all convey the same grim idea - a bloody and physical fighting of one group of human beings against another, ostensibly organized on the basis of class.

Reacting to the ill-effects of the industrial revolution - in his own way - Marx propounded a formidable new theory of society. We can extremely briefly summarize it thus: According to this theory, class struggle is the crucible through which human society marches towards a deterministic linear future. The struggle begins with the invention of private property. First comes the ancient society, in which there is a conflict between masters and slaves. Then comes the feudal society - where there is battle among the landlords and the serfs. Then comes the notorious capitalist society - where, apparently, workers (the proletariat) struggle against capitalists (the bourgeosie). The penultimate step is that of a socialist society - where workers establish a "proletarian" dictatorship. The grand drama of human history, in the Marxist imagination, ends with the formation of a communist society, where private property ends - and mankind lives in an idyllic happy state ever after.

Marx and his ideas inspired countless activists around the world, especially after - as Marx prophecied - the “socialist revolution” materialized in Russia in 1917. This iconic event, popularly known as the “Russian Revolution”, made socialism and communism quite attractive to many persons worldwide. We find that the Communist Party of India was formed just 3 years after; not to mention that the spell of communism hypnotized several men inside the Indian revolutionary movement, as well. One of the men whom Veer Savarkar himself had inducted into Nationalist revolutionism, became a convert to Communism later on - Virendranath Chattopadhyay. It is interesting to note that he met his end by getting executed under fellow communist Joseph Stalin’s orders while inside the Soviet Union. [2] Even today, there exist Marxist, Leninist political parties in India, as is well-known. Many Marxists find their place among eminent Indian historians, sociologists and so on. Clearly, Marxism is something no aware observer of society - whether in India or abroad - can ignore.

It would be safe to say that the Russian Revolution is the first and foremost event which can be regarded as an example of Marxism in action; because Marxism was not much more than an untried theory before. The Russian Revolution is worth examining, for all those who are interested, to understand the practical value (or the pathetic lack thereof) of Marxist theory - as propounded by Marx himself.

In this essay, we would mainly concern ourselves with the historical aspect of the question, rather than the philosophical aspect of the same.

The Russian Revolution happened in, of course, Russia. This is quite an important fact. Marx prophecied that the “socialist revolution” would happen after the coming of the “capitalist mode of production”, by which he meant, as we have seen - the mechanized industrialization which took place in 18th century Western Europe. Remarkably, Russia was not in a “capitalist mode of production”, by any measure. Russia of early 20th century was a peasant society - where 80 percent of the population was engaged in agriculture. [3]

Marx himself regarded Russia as an Asiatic “Byzantine-Mongol monstrosity” - in which any progressive change was not possible. [4]

Well, nevertheless, change was happening in autocratic Tsarist Russia. Tsar Alexander II enacted various important reforms, even abolishing serfdom in 1861. With the liquidation of serfdom, it would be interesting to think where Russia would have stood in the Marxist framework - it had neither slaves, nor serfs - and the newly emerged “proletariat” (workers) - was but a microscopic minority in a predominantly agricultural country. Perhaps Russia had no exact position to be placed in, really.

But inspite of that, there was no dearth of “socialists” of all feathers in Tsarist Russia. These early Russian socialists, roughly contemporary with Karl Marx himself, followed what can loosely be called peasant socialism, or 'Populism’. Its early adherents, some of them associated with the Second International, included Mikhail Bakunin and Alexander Herzen. Populists believed in a “preventive socialist revolution” - a revolution which would usher in the condition of socialism (which, for Populists, was an anarchic communistic society) without passing through the stage of capitalism - unlike what Marx had said. [5]

These Populists were inspired by the ideals of the Enlightenment - the hallmark of modernity - stretched to its most extreme and radical limits. Populism was materialist, nihilist, positivist and utilitarian - a destructive cocktail.

Needless to say, such a Quixotic adventure was never destined to reach its stipulated conclusion. In 1861, a Populist revolutionary conspiracy 'Land and Freedom' was hatched - and it failed terribly, finding no support among the Russian peasants - the class which such a revolution was actually supposed to liberate. Another was tried in 1874, this time too, the peasants themselves were not interested in the Populist programme. This was a clear sign of the radical Russian intelligentsia being so out of touch with practical realities - a trend which also showed itself in the travails of the Russian Marxist revolutionaries.

In 1878, an organization called 'The Will of the People' was founded in Russia. This Populist organization dedicated to 'socialist' revolution, was the first body of modern history specifically devoted to political terror - veritably the first terrorist organization. Contemporary Russian literateurs, including Ivan Turgenev and Fyodor Dostoevsky, were reacting to the diabolical mentality espoused by these socialist terrorists. [6]

'The Will of the People' becomes relevant in any overview of the Russian Revolution because it was the ancestor of all other terrorist parties that emerged in Russia later on - including the neo-Populist 'Socialist Revolutionaries’, 'Mensheviks’, 'Bolsheviks’, and even the Liberal 'Constitutional Democrats.'

It is customary to blame the Tsarist regime for how the situation progressively deteriorated in Russia eventually leading to the events of 1917. But it is important to keep in mind that, although the Tsarist regime was indeed repressive - yet its increasingly despotic and repressive tendencies were largely a reaction to the brutal and widespread anti-state terrorism in Russia. To see the extent of this terrorism, we may note that in 1906-1907, Russian socialist terrorists had claimed around 9000 lives - half of them of innocent civilians. [7] Tsar Alexander II, who abolished serfdom, was ironically rewarded with assassination by these 'socialist' terrorists. More than the regime itself, these terrorists had brutalized contemporary Russian social life.

But 'socialist' as they were, Populists and neo-Populists were not Marxists. Marxism emerged in Russia with the efforts of Russian intellectual Georgii Plekhanov. Other reasons were disillusionment of many with Populism, because of its repeated failure in bringing revolution. It would be interesting to examine the claim if Marxism itself succeeded in bringing a “revolution” in Russia.

Perusing historical sources, we find that what the Bolsheviks repeatedly attempted to accomplish in Russia, and what they ultimately succeeded to accomplish in Russia in 1917, was actually not revolution - but a coup d'etat.

We do not even have to look far. In 1905, Russia became a constitutional monarchy, to some extent. This terrific change in the Russian polity, came not because of a deterministic “march of human history” towards some utopia, but because the Russian army was at the time involved in a terrible war with Japan, in faraway Manchuria; and because of the Tsarship’s foolishly repressive acts which led to precipitating events like the Bloody Sunday. Yes, it was provoked in a large part by a workers' strike - but the strike itself was provoked because of the emergency situation wherein Russia was at war.

What also happened in this 1905 affair, and which is of interest to us, is that the Bolsheviks - and just the Bolsheviks, no other parties of the type - attempted an armed uprising in Moscow. [8] Equal to the task, Russian PM Sergei Witte ruthlessly crushed this Marxist mischief with a heavy hand.

Another sense in which a 'revolution' can be understood, is that it happens largely with the consent of the populace - that is, it is broadly democratic.

What happened in 1917 - in February, when the Tsardom was abolished, and a ‘Dual Government’ was established; and in October, when that "Dual Government" was replaced by an exclusively Bolshevik government - was it all democratic, in any sense?

To explain: this ‘Dual government’ was a government where the parliament had nominal power and virtually no control over the armed forces, and of course, Tsar Nicholas II (the last Tsar of Russia) had already been made to abdicate. Then who had the dominant power? In name, the power rested with the Soviets - a 'Soviet' meant a board of representatives of workers but guided and led by a radical socialist intelligentsia (Bolshevik, Menshevik, or Socialist Revolutionary). But in actuality, the power rested with the “Ispolkom” - the 'Executive Committee' of the Soviets. This Ispolkom was a 9-member group of radical socialist intelligentsia. [9] The “Dual Government” was virtually an oligarchy of socialists, where elected representatives - in the Duma (Russian parliament) - had nominal powers. This does not appear democratic, does it?

Furthermore, this was also not an indication of any deterministic "march of human history" towards a utopia - it only became possible because of precipitating events like the Znamenskii Square massacre, and most importantly, a mutiny of soldiers in the Petrograd garrison - all of which became possible only in the background of the first World War.

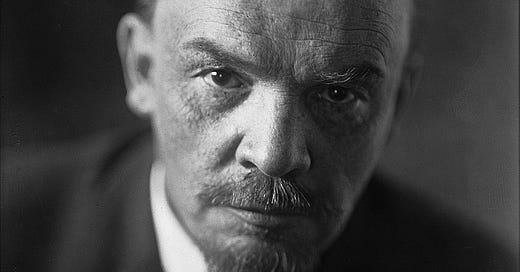

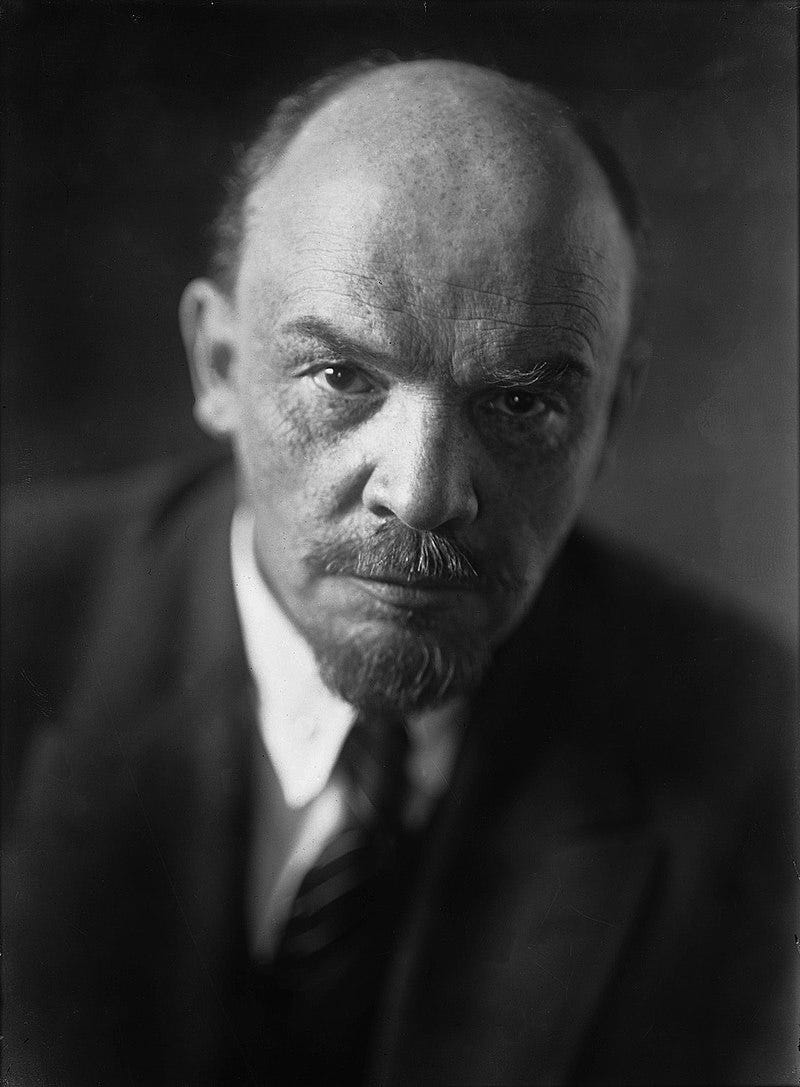

Before discussing the October “revolution” - which is what is primarily meant by “Russian Revolution”, let us first take a brief look at Vladimir Ilich Ulianov Lenin, the leader of the Bolshevik party - who is regarded as the main protagonist of October.

Himself a part of the “bourgeosie” - the landed gentry - Lenin had early contact with the Populist movement because his own brother was a socialist terrorist, and was thus executed by the Tsarist regime for the same.

Initially a neo-Populist himself, Lenin later became a convert to Marxist revolutionism. Lenin perfectly symbolized that destructive tendency which was the hallmark of Russian socialism. Peter Struve, himself a Marxist and an associate of Lenin, said about Lenin that [10] “... [his] principal Einstellung [disposition] . . . was hatred. Lenin took to Marx’s doctrine primarily because it found response in that principal Einstellung of his mind. The doctrine of class war, relentless and thoroughgoing, aiming at the final destruction and extermination of the enemy, proved congenial to Lenin’s emotional attitude to surrounding reality.” Once, Lenin defined peace as a “breathing spell for war.” [11]

Lenin was a rank-authoritarian in attitude, and the Bolshevik party was virtually fashioned in his own image - he was the dictator of the party, and others largely had to obey the commands.

When Lenin came into contact with actual workers of Russia, he was massively disappointed because the workers were not much interested in politics, so what to speak of revolution. Instead of amending his opinions, however, Lenin then tried to solve this anomaly in the Marxist framework by unintendedly himself disproving its validity.

With all the faith that Marxists tend to have in the inevitable revolution, Lenin actually admitted (though indirectly) that revolution was not inevitable. In his 1902 work 'What is to be Done?’, Lenin held that that the worker, if left to himself, would not make revolution but come to terms with the capitalist. Workers need to be actively led by full-time socialist revolutionaries who would, basically, incite the workers to revolution. [12] History does not march forward, history’s hand would have to be “forced” by the revolutionaries.

Lenin was shrewd enough to understand that inspite of Lenin’s own thesis that capitalism had already taken root in Russia [13], Russian workers were actually a microscopic minority. Hence he made concessions, in order to collect support from peasants (whom the Bolsheviks actually regarded as “petty bourgeosie”), Russian national minorities, and later on, soldiers.

To reflect, he was successful in none of these. Bolsheviks did not enjoy majority support of even workers, and had little to no representation among soldiers and peasants, on the eve of the October “revolution”. [14]

This takes us back to the question if October was democratic, and if it occured naturally, and was not a result of extraneous circumstances.

So, what actually happened in October? The whole affair began in April, with Lenin’s entry into Russia. He began preaching against the elected parliament, calling for a “socialist revolution”; and calling for an end to Russia’s involvement in the World War - not because of concern for Russia’s people, far from it - but because he wanted to start a bloody civil war in Russia, in which, after the “revolution”, Bolshevik Party would be busy in making the rest of the population submit to its rule. This is exactly also what actually happened.

Bolsheviks' funds were collected from money pouring in from the German government [15], and from the bank robberies and burgalaries the Bolsheviks carried out. [16] Till July, Lenin and his party attempted to bring down the government by provoking street riots and hysteria against the government. While at the same time, Bolsheviks succeeded in developing their own paramilitary organization - the Red Guard. With the help of the Red Guard, the Bolsheviks were successful at making the Ispolkom largely subservient to the Bolshevik Party.

After the Russian PM Kerensky lost support among the army through what is called by historians as the 'Kornilov affair', the Bolsheviks gained a new and sweet opportunity to strike after July, in October.

Lenin was anxious to carry out the insurrection as soon as possible, because it had to be done before a full-fledged Constituent Assembly was formed (as it was to be in November), since Lenin knew that democratically, the Bolsheviks would get no power. [17]

With most of the armed forces then remaining ambivalent about the parliamentary government; the Bolsheviks, with the help of troops collected through deception and other means, simply declared the Provisional Government to be deposed in the night of October 24. Parliamentarians were arrested, and government buildings occupied in Petrograd (the capital city).

To legitimize the coup, a spurious “Soviet Congress” was convened the next day, where Bolshevik-majority Soviets had extremely exaggerated representation [18]. This veritably overthrew the original Ispolkom, where Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (non-Bolshevik socialist parties) dominated. Bolsheviks, with Lenin at their head, became the masters of Petrograd, Moscow and some other big cities. With coming months, they slowly established a rudimentary hold over Russia.

Noticeable was that, unlike in February, where at least the parliament had nationwide support of the populace; the Bolshevik party had it in no measure in the events of October.

Historian Richard Pipes crisply summarizes the October “Revolution” in these words [19]:

Although it is customary to speak of two Russian revolutions of 1917 - one in February, the other in October - only the first deserves the name. In February 1917, Russia experienced a genuine revolution in that the disorders that brought down the tsarist regime, although neither unprovoked nor unexpected, erupted spontaneously and the Provisional Government that assumed power gained immediate nationwide acceptance. Neither held true of October 1917. The events that led to the overthrow of the Provisional Government were not spontaneous but carefully plotted and staged by a tightly organized conspiracy. It took these conspirators three years of civil war to subdue the majority of the population. October was a classic coup d’etat, the capture of governmental authority by a small band, carried out, in deference to the democratic professions of the age, with a show of mass participation, but with hardly any mass involvement.

Footnotes:

01. Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, p 1.

02. Vikram Sampath, Savarkar: A Contentious Legacy, p 206.

03. Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, p 4.

04. Martin Malia, The Soviet Tragedy.

05. ibid.

06. ibid.

07. Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, p 49.

08. ibid, pp 43-44.

09. ibid, p 82.

10. ibid, p 103.

11. ibid, p. 104.

12. Martin Malia, The Soviet Tragedy.

13. Vladimir Lenin, The Development of Capitalism in Russia.

14. Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, p 114, 139.

15. ibid, p 122.

16. ibid, p 108.

17. ibid, p 139.

18. ibid, pp 146-147.

19. ibid, p 113.

Good.

Quite intriguing and not-much talked perspective.