History often finds itself tangled in narratives that blur the line between institutional actions and individual transgressions. The Indian National Army (INA), a force that emerged as a beacon of India’s struggle for independence under the leadership of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, has recently come under scrutiny due to the actions of certain individuals who were once affiliated with it. However, to equate the INA’s legacy with the misdeeds of former members—after its disbandment—is not only misleading but also historically unjust.

In the past, some intellectuals and commentators have levelled accusations suggesting that the INA was complicit in appeasing jihadis. While no direct blame was placed upon the institution itself, these claims have led to extrapolations that unfairly taint its legacy. The INA, already a lesser-known chapter in India’s freedom struggle due to its complex and inconvenient positioning in mainstream narratives, has suffered further distortions due to such claims. This selective reading of history has fuelled misconceptions, allowing individuals' later actions to overshadow the broader mission, sacrifices, and inclusive nature of the INA.

As we progress with the article, some readers might object that this article is centred more around Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose than the INA itself. However, this focus is both intentional and necessary. While discussions around the secular character of the INA and other aspects of its composition have gained traction on social media—particularly on X—the real controversy began a few years ago with Sarvesh Tiwari’s talk on “Jihadis in the INA” on Sangam Talks. Since then, the critics have maintained that their concerns are about the INA and its alleged problematic elements, not about Bose himself. However, in practice, from that talk to Zalim Singh’s article and beyond, Bose has remained the primary target of abuse, criticism, and trolling on social media, especially on X.

A general perception has thus been deliberately or inadvertently created—that Bose was a pseudo-secularist, much like Gandhi and Nehru, or, as some insinuate, even worse than them. This has led to the notion that he should not be regarded as a figure compatible with Hindutva ideology or the Hindu Right. One of the key objectives of this article, therefore, is to counter this misrepresentation of Bose, which has unfortunately taken root in certain circles and, if left unchallenged, may continue to spread in the future.

It is also crucial to emphasize that while we strongly dispute any unfair generalizations about the INA, we do not, in any way, condone or defend the atrocities committed by any of its former Muslim soldiers during the Kashmir War. Their actions were reprehensible and must be judged independent of their past association with the INA. Holding them accountable, however, should not mean rewriting history to unfairly implicate an institution that had already ceased to exist.

Before starting with the detailed argument , it is important to highlight some of the major flaws in Zalim Singh’s article.

Singh employs a classic diversionary tactic by overwhelming his article with unnecessary jargon about the Kashmir War. By drowning the reader in excessive military details and unrelated historical facts, he creates the illusion of a well-researched and voluminous argument, when in reality, these details serve only to distract from the core discussion. His word ceiling is a deliberate attempt to make his claims seem factual and authoritative, when in fact, they rest on weak and misleading foundations. A strong argument does not need to hide behind an avalanche of unrelated information; it stands firm on the merit of its reasoning.

Additionally, he claims that ex-INA Muslim soldiers had an advantage in Kashmir due to their familiarity with Burma’s warfare conditions. This argument is patently absurd. By this logic, even the Indian Army would have had a similar advantage if they had employed INA officers in the Kashmir War. The supposed “advantage” only appears significant when viewed retrospectively, and before partition became a political reality , no one could have anticipated such a development. Singh’s entire line of reasoning hinges on hindsight bias rather than historical foresight, making his claims speculative at best and deceptive at worst. Moreover, Singh attempts to draw unnecessary comparisons between the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces and the INA. These were two vastly different institutions with entirely separate objectives, compositions, and historical contexts. His comparison not only lacks merit but further exposes the flawed analytical approach in his article.

Also , Singh, in his article, makes a sly remark on the Dos and Don’ts issued to INA officers, questioning the strength of the values the INA stood for by citing violations of those values committed by ex-INA officers during the Kashmir War. However, this is a flawed and intellectually dishonest comparison. The INA ceased to exist as an institution after 1945, and any actions undertaken by its former officers post-partition were entirely independent of the organizational ethos they once adhered to. Holding the INA accountable for actions committed by individuals years later in a completely different context is not just misleading but suggests a deliberate attempt to distort historical understanding. The intent behind this comparison must therefore be questioned.

Institutions are built upon principles, objectives, and collective efforts. Individuals, on the other hand, operate within those frameworks but also possess agency, which means their later actions cannot retroactively tarnish the purpose or legitimacy of the institution they were once part of. To hold the INA accountable for deeds committed by some of its former soldiers in a completely different context is akin to blaming a nation for the crimes of its ex-citizens abroad.

This article thus seeks to counter the negative perception being created in the public mind about Bose as a leader and INA as an institution due to misplaced allegations, and reaffirm the INA’s role in India’s fight for freedom while critically addressing attempts to link its cause with the actions of individuals beyond its authority.

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s leadership of the Indian National Army (INA) has often been scrutinized through a distorted lens. Among the most persistent criticisms levelled against him (as was also insinuated in the aforementioned article) are his decisions to appoint Muslim officers to high-ranking positions within the INA and to adopt Hindustani as its official language. Detractors, particularly those seeking to fit Bose into a rigid ideological framework, argue that these choices reflect a form of appeasement. However , such arguments show lack of understanding regarding the prevailing situation in SE Asia when Bose was called to accept the leadership of the INA.

In the 1st half of the article thus we will give a brief overview of the complexities surrounding the formation of the INA and the reliance on Bose’s leadership to give a unified direction to the crumbling independence movement.

FORMATION OF THE INA : Challenges & Complexities

Although the First INA was not formally established until September 1942, its foundation was laid as early as December 1941, when discussions commenced between Giani Pritam Singh and Major Iwaichi Fujiwara—chief of intelligence for the 15th Army and head of the Fujiwara Kikan—about forming a volunteer Indian force. Comprising Indian POWs and civilians in Southeast Asia, this force would fight for India's independence from British rule with Japanese support.

The plan gained further momentum on December 8, 1941, when Japanese forces landed at Kota Bharu, Malaya, marking the beginning of their first major campaign in the Second World War. The British forces in northern Malaya, including the 1/14 Punjab Regiment, were retreating southward after being outgunned by Japanese troops at Jitra. It was amid this chaos that Captain Mohan Singh, an officer of the very same 1/14 Punjab Regiment, made contact with Fujiwara and Giani Pritam for the first time on December 14, 1941.

During his initial meetings with the Japanese, Mohan Singh sought assurance that they harboured no ill intentions toward India. Singh ,the founder of the Indian National Army (INA), was still unfamiliar with the Pacific theatre and unsure of how to persuade his fellow soldiers to join the cause. Additionally, he did not know Giani Pritam well, adding to his concerns about rallying support. Another major challenge was the potential reaction of the Indian National Congress (INC) back home, particularly regarding the decision to accept aid from the Japanese. As negotiations with the Fujiwara Kikan progressed, Singh began organizing prisoners of war—dismantling communal kitchens and introducing lectures on patriotism, politics, and communal unity. Amid the evolving struggle for Indian independence, figures like Mohan Singh and Giani Pritam recognized the pressing issue of a leadership vacuum. They understood that without strong leadership, carrying the movement to its ultimate goal would be a formidable challenge.

Therefore, it is essential to highlight that more than a year before Subhas Chandra Bose's arrival in Southeast Asia, both Giani Pritam and Mohan Singh had already put forward his name during their initial discussions with Fujiwara.

Ref.- File INA 254 - Interrogation report of Fujiwara

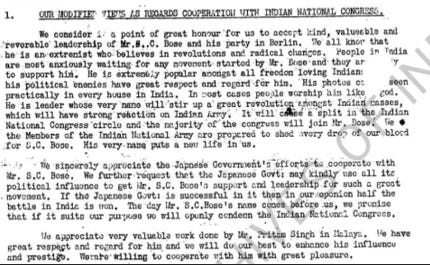

In late December 1941, Fujiwara resolved to establish a committee of Indian prisoners of war to gauge their opinions on forming a liberation army for India’s independence. The perspectives expressed by this committee may be difficult to accept for those who underestimate the profound influence Subhas Chandra Bose had on the mindset of the average Indian POW.

File INA 75

The profound impact Subhas Chandra Bose had on these soldiers—who had been part of the British Indian Army merely weeks before—is evident in their collective declaration: "We, the members of the Indian National Army, are prepared to shed every drop of our blood for S.C. Bose. His very name puts a new life into us… The day Mr. S.C. Bose’s name comes before us, we promise that, if it suits our purpose , we will openly condemn the Indian National Congress." This statement underscores how, despite strict censorship and relentless enemy propaganda, Bose’s name and heroic deeds had seeped deep into the very foundation of British rule in India—the British Indian Army.

The situation escalated significantly when Singapore, a crucial British stronghold, fell to the Japanese Imperial Army on February 15, 1942. The combined fall of Singapore and Kuala Lumpur placed over 50,000 Indian POWs under Mohan Singh’s command—an invaluable force that, if properly guided, had the potential to reshape the course of the Indian independence movement.

However, the path ahead for the First INA was fraught with challenges.

Conflicts – Political

The moment Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo made his historic proclamation of “India for Indians” on February 16, 1942, veteran revolutionary Rash Behari Bose, who had spent over two decades in Japan, sprang into action. He swiftly established the headquarters of the Indian Independence League (IIL) in Tokyo and issued its manifesto, while simultaneously working to organize and coordinate with Indian leaders across Southeast Asia.

However, many of these leaders remained deeply wary of Japan’s true intentions. As historian K.K. Ghosh notes, “their attitude was more Anti-Japan than Anti-British.” With a new power asserting control over the region, they were cautious not to antagonize the Japanese but were equally reluctant to actively seek their support. And much to their dislike , Rash Behari was doing exactly that.

At the Tokyo Conference, held from March 28 to 30, the Indian community in Japan, along with the Imperial Japanese government, proposed Rash Behari Bose as the leader of the emerging movement. However, his close ties with the Japanese government cast a shadow of suspicion over him. The deep-seated mistrust toward him, both from the civilian and military leadership, is evident in later accounts by Anand Mohan Sahay, a prominent figure in the IIL, and General Mohan Singh.

Sahay on Rash Behari Bose’s leadership

Sareen’s Indian National Army, A Documentary Study

Since many leaders from Southeast Asia were unable to participate in the Tokyo Conference, a larger assembly was planned. The Bangkok Conference, held from June 15 to 23, 1942, received official backing from the Japanese, German, and Italian governments. It also featured a message from Subhas Chandra Bose, who was in Berlin at the time. During this conference, the framework constitution established at the Tokyo Conference was formally adopted.

A Council of Action (COA) was formed, with Rash Behari Bose elected as its first president. Other key members included N. Raghavan, K.P.K. Menon, Mohan Singh, and G.Q. Gilani. However, internal conflicts plagued the COA from the outset. Mohan Singh selected G.Q. Gilani over N.S. Gill due to personal differences, while suspicions surrounding Rash Behari Bose’s close ties with the Japanese led K.P.K. Menon, a civilian representative, to align himself with Mohan Singh.

Despite these tensions, the conference resolved to raise the Indian National Army (INA) immediately. Additionally, it requested that the Japanese permit the Indian Independence League (IIL) to manage earnings from properties owned by Indians in Burma. However, the Japanese rejected this demand, arguing that the IIL was not a recognized state—a point that would later become a subject of contention.

It is significant to highlight that even at the Bangkok Conference, there were persistent appeals to bring Subhas Chandra Bose to East Asia. One of the resolutions of the conference stated: "This conference requests Sjt. Subhas Chandra Bose to be kind enough to come to East Asia and appeals to the Imperial Government of Japan to use its good offices to obtain the necessary permissions and conveniences from the Government of Germany to enable Sjt. Subhas Chandra Bose to reach East Asia safe.”

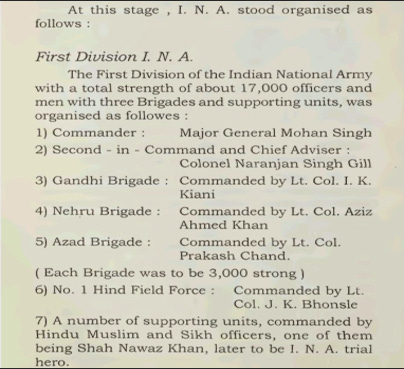

Another key resolution of the Bangkok Conference was the appointment of Mohan Singh as the General Officer Commanding of the INA. By late August 1942, over 40,000 troops had pledged their allegiance to the Indian National Army under General Mohan Singh’s leadership. Around the same time, as Japanese forces advanced closer to India’s eastern borders, the Iwakura Kikan sanctioned the formation of the INA’s first division. With this, Mohan Singh finalized the organizational structure of the First INA and appointed its top leadership.

The structure of the 1st INA

This fact directly refutes a frequently repeated allegation against Netaji—that he erred in appointing Muslim officers to high-ranking positions. This claim, insinuated in Zalim Singh’s article, collapses under scrutiny the moment we recognize that Netaji merely retained the existing structure and leadership of the First INA while establishing the Second. Zalim Singh himself provides ample evidence of the military prowess of officers such as M.Z. Kiani, I.K. Kiani, and Aziz Ahmed Khan. General Mohan Singh, who had served alongside these officers in the 1/14 Punjab Regiment, was well aware of their capabilities and accordingly appointed them to key positions in his army. In fact, it was Mohan Singh who initially designated M.Z. Kiani as Chief of General Staff. Moreover, it is important to note that the 1/14 Punjab Regiment, which formed the core of the INA under Bose’s command, consisted of nearly 50% Muslim soldiers, leaving him with limited choices. Interfering with this existing structure without a compelling reason would have been a strategic misstep.

For Netaji, these soldiers were not mere cannon fodder to be expended in war—they were future citizens of the independent nation he envisioned. Therefore, maintaining the INA’s established framework and implementing inclusive practices, such as a common mess for all ranks and communities, was essential not only for military cohesion but also for his broader goal of nation-building.

Returning to the chain of events, the situation took a sharp downturn after September 1942. Distrust between the Japanese and the Indians deepened, particularly when a group of Indian anti-aircraft gunners, assigned to the Japanese Army, were forcibly separated from Indian camps and placed under direct Japanese command.

Meanwhile, within the Indian ranks, any prospect of reconciliation between the IIL and INA leadership grew increasingly bleak. Mohan Singh faced allegations of making unilateral decisions, most notably deploying Indian troops to Burma without consulting civilian leaders. In protest, N. Raghavan resigned from the Council of Action, further widening the rift.

On 29th December 1942 , Mohan Singh was called to the office of I. Kikan and shown a letter from Rash Behari Bose. The senior Bose’s letter levelled 4 charges against Singh:-

● Singh disobeyed RBB’s direction to send up certain INA officers to meet him

● Singh was attempting to create a personal & private army of the INA

● Having cut himself from the independence movement in East Asia , Singh could not longer command the army which belonged to the movement

● Singh has wilfully & maliciously attempted to spread discontent and disaffection amongst the members of the army of the Indian independence movement in East Asia

Immediately after this , Singh was dismissed and INA Troops were disarmed. This is how the story of the 1st INA came to an unfortunate end.

Giving this context was important to make the readers aware about the often downplayed political conflicts that wrecked the first INA.

Before addressing the communal conflicts, it is crucial to recognize Rash Behari Bose’s earnest but ultimately unsuccessful attempts to reform the INA. On February 6, 1943, Rash Behari Bose proposed a restructuring of the INA to the I-Kikan, stipulating that it be placed directly under the authority of the Indian Independence League (IIL) and governed by the INA Act. While Iwakuro accepted the proposal in principle, he remained unwilling to return Indian POWs to Indian command.

Around the same time, Rash Behari Bose circulated a questionnaire among INA officers, uncovering a telling contradiction—while many were hesitant to serve under the INA, they remained resolute in their commitment to India’s independence. Shah Nawaz Khan, in his memoirs, recounts how Iwakuro responded by convening a meeting of approximately 300 former INA officers at Bidadari Camp in Singapore. Despite extensive discussions, no consensus was reached on rejoining the army. However, private conversations with officers revealed a key sentiment—many were willing to continue serving in the INA, but only under the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose.

The officers insisted on two critical conditions: no troops should leave Singapore until Bose’s arrival, and the army must remain strictly voluntary. Iwakuro agreed to these terms and assured them that efforts would be made to bring Bose to East Asia.

Conflicts:- Communal

As if the unending political conflicts weren’t enough , the even older communal divide also plagued the Indian independence movement in SE Asia. Memoirs of MZ Kiani and Shah Nawaz Khan give an account of how there was no love lost between the Muslims and the non-Muslims during the period in which the 1st INA was being raised .Kiani, in particular, notes the skepticism harboured by the Sikh community—especially Mohan Singh—towards the Muslim soldiers.

From Kiani’s Memoir

This mistrust he believed was reciprocated by the Muslims. He writes ,”Under such circumstances the Muslim officers found themselves in a very difficult situation. They were not at all happy to be placed under a Sikh, with almost unlimited power over them as POWs. They were apprehensive of a non-Muslim army marching into India with the Japanese, if a successful invasion be launched... They thus found themselves on the horns of a terrible dilemma. While at heart they were as patriotic and as keen for the independence of their country as anyone else, but they were strongly opposed to Hindu political domination of India. “

That this belief of the pro-Sikh bias was widespread can be corroborated from a British Intelligence Report referencing the same.

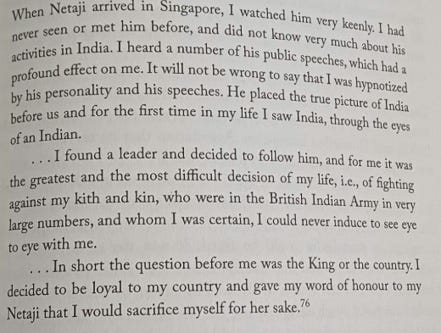

This situation arising out of mutual suspicion and mistrust changed with the arrival of Bose in SE Asia. Shah Nawaz , the one who had schemed to wreck the INA from inside , recounted in his statement during the INA trial at the Red Fort, that he was convinced that the INA 'was a genuine army of liberation' after Bose took charge of the movement in July 1943.

Shah Nawaz Khan’s statement at Red Fort Trials

These accounts of Muslim Officers of the INA , particularly those like that of MZ Kiani & Shah Nawaz Khan , clearly reveal their Islamic fundamentalist tendencies.

But the very same accounts also offer an insight into how they were willing to co-operate & work under the strong and uncompromising leadership of Bose.

This segment aims to acquaint readers with the challenging landscape in which Subhas Chandra Bose had to navigate upon his arrival in Southeast Asia. The entrenched communal divide, the mounting distrust between the Japanese and Indians, and the ongoing power struggle between Rash Behari Bose (leader of the IIL) and Gen. Mohan Singh (head of the INA) remained pressing issues. It was amidst this volatile and uncertain environment that Bose set foot on the shores of Sumatra.

Netaji, Islamic Fundamentalism & Secularism:

From the critique of Sita Ram Goel way back in 1997, to that of Sarvesh Tiwari’s and Zalim Singh’s in our own time, the impression created on the public mind has been that either Subhas Bose was not aware of the problem of pan-Islamism or he was a pseudo-secularist & Islamic appeaser, or both. Though Zalim Singh has made it clear multiple times in several of his interactions on the social media platform X, that his critique concerns only some of the ex-INA Muslims and not Bose or the institution of INA at all, still one cannot digest as to why he selectively quotes a British assessment of the INA and remarks the following :

“This raises questions about what purpose did this deliberate inclusion of Muslims in high ranking posts in the INA serve besides inadvertently providing Pakistan with the ideal cadre ready for the Kashmir invasion?”

Whatever might be the intent behind this apparent sly remark, it definitely creates the image of a naive secularist-cum-appeaser for Subhas Bose. One cannot help but wonder as to why Zalim Singh would only quote the part where the British report says that inclusion of Muslims in higher offices was to convince them against their communal perceptions about the INA( i.e. of the INA being a Hindu force) when In the very same section the report says:

“Of Bose himself it is said that one of the obvious weaknesses in Bose’s rule as the head of the PGI was his partiality first to the Bengalis and then to the Hindus. It is said he was always suspicious of the loyalty of Muslims who he believed would go over to the Muslim league if and when they reached India. Bose disliked officers who were inclined towards the ideology of Muslim League. (e.g. his court martialling of Capt M.K. Durrani)..Yet another charge against Bose is that in his PGI he appointed Hindus in charge of important portfolios wheras the only Muslim members of the cabinet were the Army members who had no hand in framing the policy of the Govt.”

From the above excerpt, it can be argued that not only Bose was aware of the Islamic tendencies and the Islamic problem, but was also working to effectively curb it in a discreet manner.

“A Brief Chronological and Factual Account Of the INA” INA papers, NAI.

One must take such British assessments of the INA with a pinch of salt, the 1000+ INA files available in the archive(made by the British) is full of their own biases and hatred based assessments and comments on the INA, trying to find one or the other reason to undermine the institution. However, the above excerpt or the idea it conveys does appear to have some grain of truth in it. We find corroboration of Bose’s awareness and knowledge of pan-Islamism in some other contexts too, one of which comes out from the interrogation report of Shankar Lal. Unknown in the popular historical narrative, Bose had started planning his move to go outside India and seek foreign aid much before his house arrest. In April 1940, Shankar Lal(Forward Bock General Secretary)went to Japan on the instructions of Subhas Bose to contact the Soviet Embassy their. Lal had talks with the Soviet and German embassies and claims to have been disturbed by the German backed pan-Islamic threat to Hindu India. It was in December 1940 when Shankar Lal was able to meet and brief Subhas Bose of his activities, what his interrogation report reads about Bose’s reply is interesting:

“Bose replied that Shankar Lal’s story of the pro-German Muslim belt on India’s borders, and in India itself, was already known to him.”

It is quite well known that Germany had strategically been supporting the political and fundamentalist Islamic entities for its own benefit. Lal claims that after his return to India, he had been cautioning people like Sarat Bose and even Dr. Moonje of the threat of an invasion of India from the NWFP which would result in communal strife and become a threat for Hindus in India. The very fact that Subhas Bose seems to have been already aware of such a problem speaks volumes of his understanding on pan-Islamism. However , it must be cautioned that Shankar Lal appears to have been deliberately and forcefully creating an impression on his British interrogators that he was disillusioned by Bose’s plan and does not subscribe to it, which is quite understandable as he was taken under arrest. In any case, this piece of information however reliable, seen in conjunction with the previous one of Bose’s deliberate inclusion of Hindus in policy-making and dislike of pro-Muslim league INA men, reinforces the point that he personally had no illusions about Islamic fundamentalism and was ingeniously working to crush it.

File No. 44/12/44-Poll(I), Home Political, NAI.

Bose’s strong views against communal Muslims is also evident in the case of ‘Bande Mataram’. The argument involving the song ‘Bande Matram’, which had become synonymous with the national struggle and revolutionary movement, is used to showcase the false image of Bose being a pseudo-secular and Islamic appeaser. The critics argue that the very fact that Bose used “Subh Sukh Chain” instead of “Bande Mataram” or Tagore’s “Jana Gana Mana” as the national song showcases his tendency of appeasing the Muslims. However, a careful analysis of Bose’s own history with “Vande Mataram” and the circumstances of 1943-45 South-East Asia shatters such misbranding. The song came under a major controversy in 1937, the Muslim side branded the song as ‘Anti-Islamic’ and communal in nature. What Bose made of such a controversy is revealed from a letter that he wrote on 17th October, 1937 to Nehru:

“Communal Muslims are in the habit of raising bogeys from time to time- sometimes it is music before mosques, sometimes inadequate jobs for Muslims and at present it is ‘Bande Mataram’. ‘Bande Mataram’ has suddenly sprung into importance probably because it was sung in Legislatures thereby demonstrating Congress victory. While I would gladly try to meet all doubts and difficulties raised by nationalist Muslims, I do not feel inclined to attach much importance to what the communalists say. If you give them the fullest satisfaction on the question of ‘Bande Mataram’ today, they will not be long in bringing up other questions tomorrow, simply in order to pander to communal feeling and embarrass the Congress.” [Netaji Collected Works, Vol.8, pp.226-7]

As to understand why Bose couldn’t reiterate this same stance when he was in South-East Asia, one needs to keep in mind the situation prevailing there. A very good account has been provided by none other than a Muslim British agent himself. This Muslim agent was apparently based in Penang, he oversaw critical movements like the formation of INA, its mobilisation and the ultimate demise. After the war, he submitted a comprehensive account to the British. Since from the very start the leaders of the movement were Sikhs and Hindus, owing to the communal distrust, a lot of Muslims were not supporting the IIL-INA movement. In order to justify their exclusion from the movement, they used to bring up a number of issues, among which the supposed communal overtone of the song ‘Bande Matram’ too was one. During the 1st INA phase, a meeting took place between Muslim representatives and Rash Behari Bose, AC Chatterjee, Lt.Col. Bhosle etc. Col. Chatterjee(who later joined Hindu Mahasabha) took a hard stance on the Muslims calling them traitors and also refused to do away with ‘Bande Matram’ while Kiani was considerate and requested concessions. No compromise was reached. When Bose tookover, he called Muslim representatives like Abdul Aziz for a meeting, and asked them as to why they are not supporting and contributing money for the movement. The Muslim side raised the issue of Bande Mataram amongst others and Netaji “told then that he will consider their objections but that they should participate in the movement.” After some persuasions, Bose succeeded in bringing Abdul Aziz(through Yellappa) in support of the movement and through him also the Muslims in Penang who collected and donated $5,0000 for the movement. Yes, Bande Mataram and Jana Gana Man(Jana Gana Mana was simply transformed into simple Hindustani-the lingua franca of most Indians in SE Asia) were substituted, but yet not in the way the Muslim fundamentalist would have wanted, as the agent writes:

“Subhas Chandra Bose ordered the substitution of another song for Bande Mataram, but in practice Bande Matram used to be sung at meetings.” [Select Documents on The Indian National Army, T.R. Sareen, pp.288]

The other objections like the use of Congress Flag and ascertaining the views of the Muslim League before committing themselves were, as apparent, not accepted and done away with. Since ‘Bande Matram’ was an easy target, the compromise was reached, yet not in a way that would fully satisfy the fundamentalist. Hence it was out of political necessity and circumstances that some steps had to be taken, the Provisional Government and the Independence movement needed funds and support to survive and strengthen, as it was working in a foreign soil far away from India and on foreign aid and support. In India, Bose could have acted along the lines of his 1937 letter to Nehru, but not in a foreign land , especially at a time when the World War was going on and there were many limitations as well as pressure to organise rapidly and fight as quickly as possible.

An important aspect that people, especially those who level such accusations, forget to consider is the political-geopolitical circumstances in which Bose was working. As to how any political/geopolitical scenario would explain, which many (especially the critiques) consider an almost idealistic projection of Hindu-Muslim unity by Netaji in his INA movement, may be difficult to understand with a superficial reading and understanding of the complexities involved. For his independence struggle which he carried on from Europe and later from South-East Asia, he needed to rely on the material support of the Germans and Japanese respectively. Be it Germany or Japan, their best bet was to support a movement/institution which was representative of all the sections of the Indian society or at least had the support and confidence of both the Hindus and the Muslims. Any other communal/sectarian movement would have hardly garnered the amount of support and recognition that Netaji’s INA & Provisional Government got. The best example is the 1st INA phase under Mohan Singh, which was regarded by the Muslims as being pro-Sikh. This internal religious schism(along with the political rivalry) too came in the way of proper mobilisation of Indians for the movement which in turn resulted in them not getting the desired respect from the Japanese as a strong organisation. On the other hand , Netaji had far more superior bargaining capabilities because he was able to prove himself as a mass leader of all the Indians, thus making him a vital and important political figure with whom the Japanese could deal with as an ally. The same thing happened in Europe wherein ultimately both Germany & Italy favoured Netaji and his organisation for the Indian Independence Struggle than that of Muhammad Iqbal Shedai, who was in Italy and was trying to impress the Italian government against Subhas Bose and his leadership. Infact , both Germany & Italy took an anti-Muslim league stand despite Shedai’s known Islamic & pro-Pakistan views. Shedai’s relations with Italy did not help him to further his own selfish and Islamic agenda because Netaji stood out as a much better leader who could command the confidence of all the Indians and had national considerations than being obsessed with the communal aspects. The fact that Germany wanted to support a movement and institution which was nationalistic in character and not the one facing internal religious schism can be understood from the conversation between Ribbentrop and Subhas Bose:

“The sensitive issue of Muslim separatism was also raised. Ribbentrop brought the issue up knowing it would have to be resolved sooner or later. Bose resorted to his standard line, namely that it was a problem caused by the ‘English and their propaganda’. He dismissed the Muslim League as a ‘backward looking clique’ with ‘plutocratic and special interests’ and portrayed plans to partition India as nothing but a ‘British manoeuvre’ akin to the partition of Ireland. Wanting to put Ribbentrop’s mind at ease, he assured him that Muslims would be guaranteed ‘absolute and complete cultural freedom’ as well as ‘economic and social equality’ in a liberated India.” [Bose In Nazi Germany, Romain Hayes , Chapter 6]

The same was the case with Japan, which since the beginning of its war activities, was urging the Indians to let go of their differences and co-operate as one with the Nipponese to get rid of the British rule.

Extracts from the Syonan Times, 8th April, 1942. ‘Indian National Army and Subhas Chandra Bose Through Japanese Sources, Vol.1’, T.R. Sareen, pp.164-166.

Despite these constraints, because of which there was a necessity of maintaining unity and harnessing support from all, Netaji did not fail to curb the Islamic tendencies in the INA. An example of which has already been provided in the British assessment, wherein it is stated as to how the court martial of the pro-Muslim league personnel, Capt. M.K.Durrani, happened. Another such instance is mentioned in the same report:

“As a result of this and other incidents, Karim Giani, an advisor to the PGI started a Muslim Movement and was supported by leading businessmen and some Muslim INA officers, for this he was strongly condemned and charged by the PGI, and taken to Bangkok from Rangoon under arrest.”

“A Brief Chronological and Factual Account Of the INA” INA papers, NAI.

Yet another instance of Bose’s reaction to a communal situation comes from the CSDIC interrogation of a civilian INA member named Juma Kian, he had converted three Sikh girls in Islam and married one of them, this caused resentment amongst the Sikhs and Hindus. Upon hearing about it, Subhas Bose called him and ‘threatened him for producing friction between Sikhs and Muslims’. The interrogation report reads:

“All the Sikhs and Hindus were his enemies due to marriage with a Sikh girl and were after his life. Even S.C. Bose did not like him...Later, was attached to IIL. Even there he proved himself unfit and was turned out by S.C. Bose.”

CSDIC Interrogation, INA Papers, NAI.

The idea that Bose, if he would have succeeded, would have indulged in Muslim appeasement and pseudo-secularism, doesn’t sit well with the facts referred to above.

The quoted examples and evidences relate to Bose’s INA phase. However , an incident, pre- 1941, from Bose’s life projects a somewhat similar picture. This time we see Bose strongly protesting against the fact that certain religious privileges were enjoyed by Muslims and Christians but the same were denied to the Hindus. In the months of November-December 1940, Bose wrote several letters to the Superintendent of the Presidency jail(where he was imprisoned) arguing for allowances and facilities to be provided for Durga Puja. He pointed out how facilities were being provided to Christians and Muslims for their religious purposes, but not the Hindus. He also charged, that the government was being lenient towards prisoners professing Islamic Faith, citing the release of the Maulvi of Murapura. Bose made it clear in one of his letters that the Government would not be moved by his protest(against detention) via a voluntary fast, because he was not a “Muhammadan by faith”. In short Bose championed the Hindu cause and called out the appeasement and exclusive privileges for Muslims, in religious matters and otherwise.

“It is surprising and painful that all this is happening under the aegis of a ‘popular’ ministry. I have been watching how the self-same Ministry has been behaving in the case of citizens professing the Islamic faith-particularly when they happen to be members of the Muslim League.” [Netaji Collected Works, Vol.10, pp.186]

“This fast will have no effect on the ‘popular’ ministry, because I am neither the Maulvi of Murapara, Dacca nor a Muhammadan by faith.” [Netaji Collected Works, Vol.10, pp.187]

Letters Of Subhas Chandra Bose, Collected Woks Vol.10, pp.183 & 194

Above: Requesting for equal religious rights for Hindu prisoners.

Below: Differential attitude of the government, in regards to D.I. rules, for Hindus.

Hence, a careful analysis of historical accounts and records suggest that not only Bose was aware of the Islamic problem, but contrary to the critiques and the perception generated from Zalim Singh’s comment, he was far from being a naive pseudo-secularist. Instead, he crushed the communal-Islamic activities, whenever those affected his institution and hampered the independence movement. While at the same time he was pragmatic in his approach, and tried to come to an understanding with the Muslims who were indirectly harming the momentum of the INA & PGI by not joining and supporting the movement. Bose was required to present a united front and at the same time tackle the communal problems to make his movement successful, which is exactly what he did.

Netaji’s Vision & Post-INA realities:

As apparent, from Zalim Singh’s article or any such type of critiques, the general reaction invoked on social media is that of revulsion towards the INA. Such a reaction not only comes from those who can be called as “nobodies” on the social platforms, but also from various intellectuals with a good amount of followers. The general trend followed in these critiques, from Sarvesh Tiwari’s “Jihadis within Azad Hind Fauz” to Zalim Singh’s articles, is recounting the names of the INA officers who went over to Pakistan and held military commands against India in the first Indo-Pak war(as well as recounting the atrocities done) and then questioning the secular character of the INA by making the events of 1947-48 as the base of their argument.

However, a much better approach could have been to cite such cases of “jihad” or atrocities committed by the Muslims(who were numerically superior than the Hindus) during the INA phase itself, or much better, during the time when Subhas Bose was in command. However, apart from few anecdotal references here and there, nothing substantial has ever been produced, from which it can be proved that the INA was a Muslim appeasing or a jihadi organisation or that Netaji committed a great blunder by organising such a force which would have been dangerous for India if it would have won in the Imphal campaign. As already pointed out in the introduction of this article, one must distinguish between an organisation and the actions committed by some of the members of the organisation in their own personal capacity and especially after the particular organisation has ceased to exist. A natural question would then follow that if INA was indeed a secular force committed for India and Indian Independence, why did its officers like Habibur Rehman and M.Z. Kiani commanded a Jihadi war against India? Doesn’t it prove that they never truly did away with their communal instincts? The answer to such type of questions is simple, it is foolish to think that INA was some sort of an inner purification programme, wherein the communal instincts picked up by its members over decades, from their upbringing and circumstances, would somehow get magically vanished. What INA infact represented was a national institution, which through its very intrinsic structure and the ideals it contained( embedded through the charismatic leadership of Subhas Bose) enabled or lead its members to sideline their communal instincts and work together for a larger goal of national importance. There definitely existed a few cases where this did not hold true, but as a whole it did. There are many examples to prove this, one such is Shah Nawaz Khan himself. Upon studying his statement in the Red Fort Trials and his own memoir, it is clear that during the INA’s formative years, he was driven by communal instincts or Islamic instincts, he wanted to join the INA only to wreck it from within and stop it from giving an advantageous position to the Sikhs and the Hindus. However after Netaji’s arrival, the reorganisation he carried out, the spirit of Independence he invoked and the euphoria of a free India and INA being an army of independence( which energised the entire South East Asia) convinced Shah-Nawaz and many like him to sideline all their prejudices, communal instincts and fight dedicatedly for the movement. Now this transformation doesn’t really have to be taken to mean a complete internal metamorphosis, but it does evidences that INA as a whole(as long as it survived) remained an institution dedicated for a larger National goal, despite the multitude of imperfections that may have plagued its individuals. One must not need take Shah Nawaz’s words for it, the history as it played out is an evidence in itself. Shah Nawaz Khan fought bravely while commanding the No.2 and No.3 battalions of the Subhas Regiment, he risked his life and never once did he tried to “wreck” the INA which he had planned to do earlier out of his fundamental communal instincts. On top of that, he was unapologetic about his participation in the INA and loyalty for Bose in the Red Fort Trials, despite knowing very well that he might be hanged. The same unapologetic demeanour can also be seen in M.Z. Kiani and Habibur Rehman, both of whom despite going over to Pakistan, always spoke with respect & admiration for INA, Netaji and the fight for Indian Independence. It is quite surprising as to how they were able to maintain this stand knowing that Pakistan had no love for INA. The Muslim League newspaper “Dawn” had tarnished INA’s image, then Pakistani prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan had blamed former INA men for the massacre of Muslims in Jammu.

Excerpt from Shah Nawaz Khan’s statement in the Red Fort Trials

Hence , it would not be outrageous to claim that the continuation of INA & PGI in free India, would have definitely kept many such communal elements in check, and the overriding euphoria of victory, Independence and National reconstruction would have oriented the people towards larger nationalistic goals.

However, from the surrender of Japan on 15th August 1945 to India gaining independence-cum-dominion status on the same day of 1947, the circumstances had changed drastically. INA no longer existed, Bose had disappeared and was not in India to finish his unfinished work of reorganisation, the baton of this institution and the movement as a whole naturally passed on to the Congress leaders and they made little to no effective use of it. Critics generally scoff at the very idea of taking into account the circumstances that prevailed and the blunderous choices made by the political leadership. They tend to strawman such analyses, branding it as an attempt to whitewash the crimes of ex-INA jihadi Muslims, and maliciously exploit the emotions of the people, thereby , goading them into looking at any such consideration with loathing. Even if such considerations are taken into account while completely admitting the war crimes committed or the jihadi mentality exhibited by some Muslim ex-INA officers after independence. The end of the INA and the absence of its commander, the atmosphere of 1946-47 India charged with communal politics of the worst kind, the inevitability of Partition post August 1946, the non-reinstatement of INA in the army and little incentives for INA soldiers; all these circumstances combined created an atmosphere for the repressed tendencies of Muslim fundamentalists to gain ground and aided them to act accordingly. Let us read what the devil of the debate, M.Z. Kiani, himself wrote about all this:

“the long-sought independence in sight, the principal political parties in India got their goal of independence, but decided also to partition the country into sovereign states-India and Pakistan. This automatically split the INA which then ceased to exist as a body. Those of us whose homes were in the territories comprising Pakistan, now acquired a new nationality and we geared ourselves loyally our obligations as citizens of the new country and the state. There was no conflict whatever in our minds regarding this as the major goal of our struggle in the Far East was the freedom of India and then to leave the people to decide with their free will about the type of constitution they may wish to have under the new dispensation.” [M.Z. Kiani, India’s Freedom Struggle and the great INA, pp.xiv-xv]

At another point he wrote:

“The spirit of the INA was extinguished after the partition of India and the emergence of the two independent states of Pakistan and India. It had done its job and had no raison-de-etre any longer.” [M.Z. Kiani, India’s Freedom Struggle and the great INA, pp.203]

A similar kind of a story can be seen in the case of Habib ur Rehman too, the circumstances combined with little to no effort from the Government to make use of the INA and provide them with incentives, created a similar situation for Rehman. Though in Rehman’s case, his choice seemed to have been even more inevitable, his side of the story was provided by Anand Mohan Sahay(a minister in the Azad Hind Government) in his deposition before the Khosla Commission Of Enquiry:

“He with my consent wanted to leave. He said: Mr. Sahay, I would like to live here but you see how things are happening. Two of my cousin sisters, young girls were abducted in Kashmir and if I stay here who knows what will happen to me. I knew what the situation was and so by giving him a Hindu name, I booked his passage from Delhi to Srinagar.”

Khosla Commission, Evidence Of Witnesses, Vol.11, NAI

Habibur Rehman, despite working for the Pakistani Government at that time and hence naturally being limited with his words, spoke with nothing but utmost respect for Netaji and the INA to the Japanese historian Tatsuo Hayashida in 1968:

“Finding that their hold over the services of the country had loosened and the people wanted them now to go home, the British rulers decided to quit India on 14.8.1947. Thus the stand of the INA and its leader in particular and the people of India in general was fully vindicated, It is indeed a great tragedy that Mr. Bose had not been able to see for himself the fruits of his life-long freedom struggle, Many in Bharat still believe that he is alive and will turn up some day, How much we wish that he had come back alive, in that case it is more than certain that he would have occupied a dominant position in Indian politics, Thus the relations between Bharat and Pakistan would have been cordial rather than embittered as they are today, He was known to be a most judicious and fair-minded leader. However, the blaze of freedom left by him is still burning and will continue to inspire the freedom-fighters.”

All of this might yet again get twisted/strawmanned or declared as an apologia of the jihadists by the similar tactics of the critiques as was described above. However, serious and unbiased readers would hopefully appreciate the detailing of these circumstances, which might provide them with a better picture. The war crimes committed by the ex-INA men and their fundamental communal instincts have never been our points of contention. Those acts are inhumane , condemnable and reprehensible. However, in the communal scheme of things, if the entire INA saga has taught us anything it is that a capable, competent and charismatic leadership and institutions based on national ideals and robust structure, can do much better in orienting even people with myriad of imperfections into working for a national cause by influencing them towards it. In short, act as a check against separatist tendencies. The world and its working is complex in nature and hence must be understood and studied in that sense only, without reducing it to simple generalisations or extremities. If there were people like M.Z. Kiani and Habibur Rehman, who owing to their communal instincts went to Pakistan and acted in accordance with their fundamentalist tendencies, there was a Shah-Nawaz Khan who despite being born in Pakistan(and some of his relatives working in the Pak army) chose to remain in India and serve the country, the Congress also provided Shah Nawaz this opportunity by giving him the incentive to join Congress, which he gladly took . Also , there were other Muslim ex-INA and PGI men who stayed back and served under the Indian Government at top positions, the men being referred here are Abid Hassan and Col.Mahboob Ahmad. While Shah-Nawaz remained in check before the public eye and under the government machinery, an almost open field was provided to those other nefarious ex-INA elements by providing them with the option of Pakistan and thus inviting further harm upon our own nation. Hence , demeaning the institution of INA or Netaji for that fact who was largely successful in dealing with this problem, is nothing but deplorable and outright pathetic. As far as Netaji is concerned, Kiani like many others seemed to have no doubt as to how things would have panned out under Bose’s tutelage:

“Posterity must indeed wonder about the quality of political leadership that allowed such a situation to develop. It is inconceivable that with a man of the calibre of Mr Subhas Chanra Bose, such a calamity would have befallen the Indian people.” [M.Z. Kiani, India’s Freedom Struggle and the great INA, pp.211]

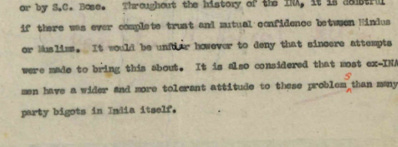

As far as the secularism of the common ex-INA man is concerned. The CSDIC officer G.D. Anderson, an arch enemy of both Bose and the INA, who on account of being British left no opportunity to demean the struggle of the INA; wrote something sensible while being uncharitable at the same time:

“Throughout the history of the INA, it is doubtful if there was ever complete trust and mutual confidence between Hindus or Muslims. It would be unfair however to deny that sincere attempts were made to bring this about. It is also considered that most ex-INA men have a wider and more tolerant attitude to these problem than many party bigots in India itself.”

“A Brief Chronological and Factual Account Of the INA” INA papers, NAI.

The segment can be concluded by quoting what Smitha Mukherjee rightly said on the Sangam Talks youtube channel in her rebuttal to Sarvesh Tiwari’s critique of the INA:

“When it comes to Islam, caution is well in place, but prejudice doesn’t help get anywhere, realistically speaking, only clear-sightedness does.”

Legacy Of The INA:

Zalim Singh, in his article and interactions on the social media platform-‘X’, has talked about the military performance of the INA and as to how they failed on the battlefield. Again, he stated what is largely speaking a fact. The INA along with the Japanese forces failed in their major objective of capturing Imphal. Plagued with the issues of insufficient supply, the worst timing of such an offensive when the tide of war had already started turning, the onset of monsoon, strategic blunders on the part of the Japanese and betrayal via desertions; all these factors lead to the retreat of the INA-Nipponese forces. Though the mention of this military failure along with the issue of the ex-INA Muslims, again created a negative impression on the mind of casual readers and also gave the opportunity to the usual trolls with a clear distaste for Subhas Bose and the INA, to demean this glorious and most critical chapter of the Indian freedom struggle. In this section, facts will be provided, which will prove that the INA did not fail completely. The INA was indeed able to achieve the larger objective/goal for which it was made, although the fulfilment of such an objective happened in a different circumstance and time. To be able to appreciate such a claim, one needs to understand that the goal of the INA wasn’t purely on the military lines, it was much more strategic in nature than simply winning a few campaigns via direct confrontation. It was kind of politico-militaristic in nature. Hence , a military historian or a person obsessed with military history can surely do an analysis of the same nature for the INA, but to judge it on the basis of it is both unfair and dishonest , because such an analysis would lack a holistic approach which is essential in the case of the Indian National Army.

To understand the larger plan that Netaji had for the INA, one needs to go back to 1941, when Bose was in Kabul, what he thought along the lines of military opposition to the British is clear from the talk he had with Alberto Quaroni at the Italian legation in Kabul:

“According to Bose India is morally ripe for the revolution, what is lacking is the courage to take the first step: the great obstacles to action are on one side the lack of faith in their own capabilities and on the other the blind persuasion of British excessive power. He says that if 50,000 men, Italian, German, or Japanese could reach the frontiers of India, the Indian army would desert, the masses would uprise and the end of English domination could be achieved in a very short time....... He would like also to intensify internal propaganda for desertion from the army, not sporadic desertion but mass desertion of entire divisions, and this would naturally be a very good thing.” [Netaji Collected Works, Vol.10, pp.35-36]

In his secret memorandum to the German Government on 9th April of the same year, he again made this point, after giving a critical examination of the number of British to Indian troop disparity in India:

“As already stated above, British prestige in India is shattered as a result of the many defeats which the British have suffered in the pre- sent war. As a matter of fact, after the fall of France in June 1940, the Indian Army was in a mood in which there was utter lack of confidence in British military strength. That was the proper psychological moment for a revolution, but it was not availed of by the Indian people. A similar opportunity will come again when Britain receives another severe blow at the hands of the Axis Powers. When the opportunity comes again and if it is properly utilised revolts can be brought about in the Indian section of the Army, in spite of the British personnel of the officers In that revolutionary crisis, the British Government will have only the British soldiers to fall back on. If at that juncture, some military help is available from abroad (i.e. a small force of 50,000 men with modern equipment) British power in India can be completely wiped out.” [Secret Memorandum to the German Government, Collected Works Vol.10]

In mid 1943 when Bose had reached South-East Asia, he was better equipped with resources, i.e., thousands of soldiers and the geographical position too favoured him, he tookover the command from Rash Behari Bose on 4th July and on 9th July in a mass meeting held in Singapore, he declared his plan as to how INA would bring about the Independence of India:

“The time has come when I can openly tell the whole world, including our enemies, as to how it is proposed to bring about our national liberation. Indians outside India--particularly, Indians in East Asia-are going to organize a fighting force which will be powerful enough to attack the British Army in India. When we do so, a revolution will break out, not only among the civil population at home. but also between the Indian Army, which is now standing under the British flag. When the British Government is thus attacked from both sides- from inside India and from outside--it will collapse and the Indian people will then regain their liberty.”

Excerpt from Netaji’s speech on 9th July, 1943.

Well the “enemies” whom Bose also wanted to hear his declaration, were already in fear of this problem. The British and the General Headquarters(GHQ) of the British Indian Army had visibly shaken on the prospect of the above quoted plan becoming a reality, much before Bose had even arrived in South-East Asia. Upon receiving information about the organisation of an army by General Mohan Singh in collaboration with the IIL and the Japanese, the British made several reports. One such report made on 6th November, 1942 read:

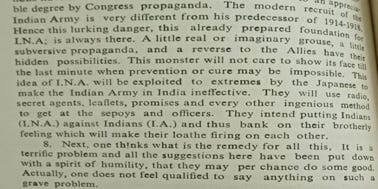

“The modern recruit of the Indian Army is very different from his predecessor of 1914-1918, Hence this lurking danger, this already prepared foundation I.N.A; is always there, A little real or imaginary grouse, a little subversive propaganda, and reverse to the Allies have their hidden possibilities. This monster will not care to show its face till the last minute when prevention or cure may be impossible. This idea of I.N.A. will be exploited to extremes by the Japanese to make the Indian Army in India ineffective.....Next, one thinks what is remedy for all this, It is a terrific problem and all the suggestions here have been put down with a spirit of humility, that they may per chance do some good. Actually, one does not feel qualified to say anything on such a grave problem.”

File No. L/WS/1/1576. India Office Library London.

The portion has been deliberately highlighted, one usually doesn’t come across such an informal and superlative language in official records, however the gravity of the situation couldn’t have been stressed upon without a clear cut statement like this. However , the report by GHQ prepared for the General Officers Commanding even outdid this one, made on 18th March 1943, this report went on analysing the British Indian Army of the pre-war period and branded it as “in practice still a mercenary army”. The report records as to how the material considerations, which had kept this mercenary army loyal, are eroding away in face of the Nationalist propaganda and hence this fresh army raised during the war is highly prone to the possibility of an internal revolt. Infact, the report is already listing various isolated cases of desertions under INA propaganda and hence requesting to dispel any complacency. As a counter subversive strategy, a kind of subtle brainwashing when read between the lines, the report suggested:

“It is also essential that efforts should be made continuously to impress on men, especially of the recently introduced classes, that they are fighting in India’s interest and that a Japanese victory would be disastrous to their own future.” [File No.601/IC/469-H, Select Documents on INA by T.R. Sareen]

As apparent from the above reports, the larger plan for the INA envisioned by the leaders in South-East Asia and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose himself, was an effective one, a plan which even the British were finding impossible to deal with. The only hope for the British was to continue the propaganda in the Indian Army and censor every piece of news and information about Subhas Bose & the INA from reaching Indians and especially the soldiers. However , all these measures were only good until the INA would have penetrated deep enough in the Indian territory, fortunately for the British, this never happened and the soldiers could only get a wind of the INA and that too only those who were actually on the front lines. However it must be mentioned that even if the INA never penetrated deep enough in the Indian territory to be able to properly influence the soldiers, some desertions nonetheless happened in the British-Indian Army, especially in the Arakan sector:

“This position was surrounded by Misra's JIFS and, contact was made (by a subterfuge) with Jem Gajendra Singh. Misra held parleys with this VCO and persuaded him to surrender his entire troops, of 26 men. The men were sent to the rear and thence to Rangoon where they were all 'incorporated in Bahadur Gp. GaJendra Singh was commissioned into the INA. During the subsequent fighting at Bawli/Ngakyedauk over l00 British/Indians were made POW and lectured to by Misra's JIFS. Most of them volunteered for the INA and were sent to Rangoon.”

The end of the war brought relief to the British in this regard, but their momentous joy was soon about to turn into fear and rock the very basis of their rule, the INA soldiers were arrested and brought to India. The British made the blunder of putting them on trials with full publicity in the Red Fort. Shah-Nawaz, Prem Sehgal and Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon were charged with waging war against the King apart from other charges. In the meanwhile, the story of the INA spread like wildfire to the remotest areas of the country and especially deep within the British Indian Army, Air Force and Royal Indian Navy. The Comander-in-Chief of the British Indian forces -Claude Auchinleck , the provincial governors ,the Intelligence Bureau, Military Intelligence, Viceroy Wavell etc. panicked seeing the tremendous wave of sympathy for the INA amongst the British Indian Army, reports after reports started pouring about Military men attending functions and programmes on the INA openly, the ratings of the Royal Indian Navy donating money in the INA funds etc. After a few months, revolt was seen in the Royal Indian Navy(a topic which deserves a separate article in itself) aided with that of the Air Force. The Commander-In-Chief ceased to have any faith in his own Army in India, the same was true for the British Prime Minister Clement Atlee. The voluminous amount of records and documents regarding this deserves a separate article or a separate book at best. However , to understand the gravity of the situation prevailing at that time, and the extent to which the INA had influenced and brought the Indian Army to the verge of a revolt, one must read this particular excerpt from a report that the C-in-C Claude Auchinleck wrote to Chiefs of Staff Committee in London, requesting them to dispatch more British formations to India in view of increasing sympathy with INA in the army and an eminent danger of revolt:

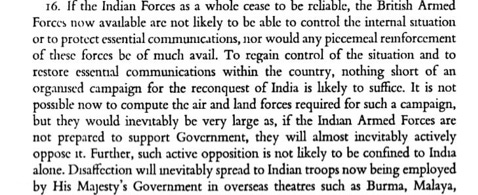

“If the Indian Forces as a whole cease to be reliable, the British Armed Forces now available are not likely to be able to control the internal situation or to protect essential communications, nor would any piecemeal reinforcement of these forces be of much avail. To regain control of the situation and to restore essential communications within the country, nothing short of an organised campaign for the reconquest of India is likely to suffice.....Further, such active opposition is not likely to be confined in India alone. Disaffection will unevitably will spread to Indian troops now being employed by His Majesty’s Government in overseas theatres such as Burma, Malay, Java and the Middle East with serious repercussions on the attitude of the peoples of those countries. Afghanistan also may well throw in her lot with the Frontier tribes and the Mussalmans of North-Western India.”

Transfer Of Power Vol.6, Document 256.

The strong language in this excerpt, particularly the reference to the “reconquest of India,” speaks volumes about the impact of the INA. When this aspect is highlighted on social media, it often attracts dismissive remarks, with some mockingly referring to it as merely a "moral victory." However, if a so-called moral victory meant that the British were compelled to hasten their departure from India due to a loss of confidence in their armed forces and the looming threat of rebellion—largely influenced by the INA—then it is a victory worth acknowledging with pride. In fact, this outcome aligns closely with the INA’s broader objective, even if it unfolded under different circumstances than originally envisioned.

Speaking of “moral victory”, Nawaz-Sehgal-Dhillon faced no consequence as the sentences provided to them had to be revoked and the reason for it was again provided by Auchnileck to Viceroy Wavell:

“In taking the decision to show clemency, the whole circumstances past, present and future had to be considered and was[were]so considered most carefully and over a long period. The overriding object is to maintain the stability, reliability and efficiency of the Indian Army so that it may remain in the future a trustworthy weapon for use in the defence of India and, we hope, of the Commonwealth as a whole.”

Auchinleck to Wavell, 13th February, 1946.

As already mentioned, this is only but a small portion of the vast documentation available on this aspect. INA did win some battles despite the circumstances set against them, they advanced considerably in the Arakan Sector, held off British assaults on their own at many points, advanced into Manipur and raised the tri-colour on the Indian soil at Moirang on 14th April, 1944. However, INA did fail to advance considerably to start a revolution during its 1944-45 campaign. Though it still succeeded in its objective and realised victory by turning the morale of the armed forces and setting a stage of rebellion against the British, which made them ultimately leave Indian quickly. As one of the most widely respected Historians of the era, Dr. R.C. Majumdar, rightly observed in his third volume of the “History Of Freedom Movement In India”:

“It is likely, therefore....the formation of I.N.A. by Subhas Bose...had shattered all hopes of using Indian sepoys in future against Indian rebels, and hence a paramount need of permanently locating such a powerful British army in India as the British could no longer afford to do so....the fact was obvious that if the British could not count on the loyalty or allegiance of the sepoys and had to rely solely or even mainly on British troops, they might as well give up all hope of ruling India; for they had not the resources, either in men or money, to fight against the resurgent masses of India.”

R.C. Majumdar, History Of Freedom Movement In India, Vol.3

CONCLUSION

The legacy of the INA under Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose remains a critical yet often misrepresented chapter in India’s struggle for independence. While some former Muslim INA members later engaged in actions that were reprehensible , these individual transgressions must not be conflated with the ideals and objectives of the institution itself. The INA was not merely a military force—it was a revolutionary movement that sought to dismantle British rule and inspire a sense of national unity among Indians, transcending regional, religious, and caste divisions. Its impact went beyond the battlefield, igniting a spirit of resistance and self-determination among the Indian masses and shaking the foundations of British colonial control.

Bose’s leadership, often mischaracterized through selective historical interpretations, was pragmatic, strategic, and deeply rooted in the realities of India’s geopolitical landscape. His vision for the INA was not driven by appeasement or ideological compromises but by the necessity of forging a united front against colonial oppression. By incorporating diverse elements of Indian society into the INA, Bose sought to instil a shared national consciousness that prioritized India’s liberation over sectarian differences.

Despite its military setbacks, the INA played a crucial role in the ultimate downfall of British rule in India. The trials of INA officers at the Red Fort in 1945-46 sparked a nationwide wave of sympathy, fuelling mass protests and widespread unrest, including uprisings within the Royal Indian Navy and sections of the Indian Army. The British, recognized that their control over India was rapidly eroding. The INA’s influence on the psyche of Indian soldiers, who had long been the backbone of British military power in India, proved decisive in hastening the end of colonial rule.

The deliberate distortion of history by some individuals through selective interpretation raises serious questions about their true motives. Is their goal merely to exploit the Hindu cause for personal gain? We hope this article brings a sense of objectivity to those who have persistently raised this issue on Twitter, often levelling unfounded accusations against us and other esteemed researchers of exploiting Bose’s legacy for personal gain. In reality, it is they who shy away from in-depth discussions, relying on selective narratives rather than engaging with the complexities of history.

As history continues to be debated and reinterpreted, it is essential to counter distorted narratives that seek to discredit Bose and the INA by fixating on the later actions of certain individuals. The INA must be remembered for its true essence—an institution born out of the sheer determination to see an independent India, driven by the sacrifices of thousands who put their lives on the line for the nation’s freedom. Recognizing its contributions is not just an act of historical justice but also a reaffirmation of the ideals of courage, unity, and resistance that shaped India’s journey to sovereignty.

Acknowledgement:

This article couldn’t have been completed without the help and suggestions from my friends and fellow Bose enthusiasts Aditi(X account-@Aditi_Indian_) and Ritesh (X account-RiteshS13557168). They have been involved in this from the initial discussions to the final write-up. My heartfelt thanks to both of them.