A view in vogue within the Indian Right that is ignominious of the past is regarding the policy view of Indians during the colonial era. It is not to say that they believe that their ancestors did not write anything, but as those writings are not easily accessible to them. This article will shed light on the views of Indians during the colonial era, on topics they felt were of importance. I would express my opinion as minimally as possible and give a commentary on the possible reasons for their views, ideological or otherwise.

The event of those times which I would like to focus on, as they captured the attention of intellectual “Indians” during those times were what was known as, “The Eastern Question”.

The Eastern Question

The Eastern Question developed in the aftermath of the beginning of the Great Game. The Great Game was a competition between Britain and Europe over the crown jewel of the British Empire, India. After the end of the Crimean War(1853–1856) which the Russian Empire lost, their dream of expanding into the Mediterranean was dashed. They now sought other avenues of expansion and expanded into the Caucasus and central Asia. They were expanding into the Caucasus since the early 19th century, but now it was imperative and was completed by 1864 at the expense of the Persian Qajars and Ottoman Turks.

The expansion in Central Asia led to the Great Game and these developments led the British to think whether to support the Ottoman Turks against Czarist Russia and tackle them in Afghanistan and Central Asia or to let the Russians expand into their natural territory, the Mediterranean and Anatolia, at the expense of the Ottomans. This issue led to many different views of “Indians” from one community as an opposition to the view of the British. The majority Indian community did not really care for the issue.

(The Eastern Question)

I will now present the views of certain individuals on this issue,

James Long[1]

The Briton’s view on the Eastern question is borne out of pragmatism. It describes the Crimean War as the hastening of Ottoman decline and the reforms as doing nothing but failing to resuscitate a corpse. The British policy of supporting the Ottomans has led to the endangering of the crown jewel of of the British Crown, India, as the Russian Juggernaut, given its imperialist expansionism was expanding into the Mediterranean, after the loss during the Crimean war, they expanded in Central Asia and now have reached the doorstep of India. He urges the British to disown their Ottoman ally and let the Russians expand into their natural territory.

He acknowledges the concerns of the Conservative party regarding the Muslim subjects of the crown and their outrage towards Britain, if they were to abandon their Ottoman ally, the leader of the Muslims all over the world as Caliph. He goes on to point out how the Ottoman Caliph’s support for the British during the 1857 revolt did not stop the Indian Muslims from fighting against them, and they became their most dreaded enemies. He argues proactively for abandoning the Ottoman Empire but comes to change his view later.

Jamaluddin Afghani[2]

Jamaluddin Afghani in his Letter on Hindustan(1883), states, the British are a colonizing force who want to become the masters of all roads to India which is why they tried to seize passes in Afghanistan and Baluchistan. They repudiated Napoleon in Egypt and later took over from the Ottomans. His argumentation is similar to that of an anti-Colonial Pan-Islamist. He goes on to say that all inhabitants of India irrespective of religion, caste or race hate the British. He argues that the domination of the British over India is ‘weak’. This letter was written after 1857. He critiques the monetary policy of the British for destroying Indian trade and for levying high taxes on natives.

The British takeover of Egypt led to great anger within other European powers due to their mutual interests in the Nile Valley and Muslims around the world as it came under the dominion of the Ottoman Caliph. This he warns would lead to large-scale revolt at the hands of the Muslims due to them sharing veneration for the current Ottoman Sultan who was the caliph for the Muslim world. If the British tried to establish dominion over other parts of the caliphate, Indian Muslims and Hindus would rise to fight the British in Hindustan.

The intellectual Hindus of those times were prolific writers, and they did not write a lot about the Ottoman Sultan or the Caliphate.

Salar Jung II[3]

In Europe Revisited, the author comments on the state of the Ottoman Empire as the sick man of Europe and the threat of Russians taking over the Bosphorus strait, the British are the “true friends of Turkey” discouraging and being a roadblock towards reforms which would help save the Ottoman Empire. He also argues for the Ottomans to find newer allies due to a new set of politicians emerging in Britain who seek to disengage from the Mediterranean and want to leave the Ottomans to their fate, and no self-respecting nation should accept it.

He states the uses of the Ottoman Empire to the British and how they have used the Caliph to ensure that the 1857 revolt did not spread to other areas as the Caliph held significant influence over a portion of the Indian populace and this helped the British ensure their control over India. He states how the British Empire has 50,000,000 Muslims as subjects and those subjects have been loyal to their great White Empress. He indicates how the British Empire is the largest Muslim Empire as it has the most Muslim subjects, and therefore it is in the interest of the British Empire to ensure the continuance of the Ottoman Empire.

Salar Jung II’s opinion is similar to a Young Ottoman who wants Turkey to revitalize and ensure a glorious future for the Ottoman caliphate. He warns the Ottomans regarding their alliance with the British and questions their motives. A typical Pan-Islamist given his call for the ummah to find an Amir ul momineen(Commander of the Faithful).

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan[4]

He openly called the British Empire, a Muslim Empire as 50 million Muslim souls recognized the British crown as their sovereign. He disputed the fact regarding the Ottoman Emperor being the Caliph of all Muslims as he did not hold dominion over all Muslims and was not their sovereign. He stated that for him to be the Caliph of the Ummah(Global Muslim community), he would need to be the sovereign of all Muslims, and he is not the sovereign of all Muslims.

He does agree with the proposition that all Muslims share an affinity towards the Ottoman Sultan as he is a Muslim sovereign and a co-religionist, but this does not mean that the Muslim subjects of the British Crown have dual loyalties and are loyal subjects of the Empress. Even though the British Empire is a Christian one, with a Christian sovereign, they have allowed the Muslims to follow their faith with complete freedom and have not interfered with their internal religious matters, and haven’t imposed any judicial system onto them which the community considers foreign and of secular origin.

He was a Muslim Loyalist and sought favors from the British for his religious community. He was also the progenitor of the idea of the Two-Nation theory, in which he considered the Muslims and Hindus to be two distinct nations. He devoted much of his intellectual career to ensuring the modernisation of the Muslim community through modern education and ensuring that the Muslim community remained loyal to the British.

Footnotes:

“The Position of Turkey in Relation to British Interests in India” originally appeared as James Long, “The Position of Turkey in Relation to British Interests in India,” Journal of the East India Association 9 (December 1875): 179– 209.

“Letter on Hindustan” originally appeared as Sheikh Jamaluddin Afghani, “Lettre Sur l’Hindoustan,” L’Intransigeant, April 24, 1883. Translated here by Sravya Darbhamulla.

“Europe Revisited” originally appeared as Salar Jung II [Mir Laiq Ali Khan], “Europe Revisited II,” Nineteenth Century 22, no. 128 (October 1887): 500– 10.

“The Caliphate” originally appeared as Syed Ahmed Khan, “The Tehzib- ul- Akhlak — the Caliphate,” Aligarh Institute Gazette, September 11, 1897, 26– 32. The essay was subsequently reprinted as “The Sultan and the Caliphate,” Pioneer, September 19, 1897.

Reference:

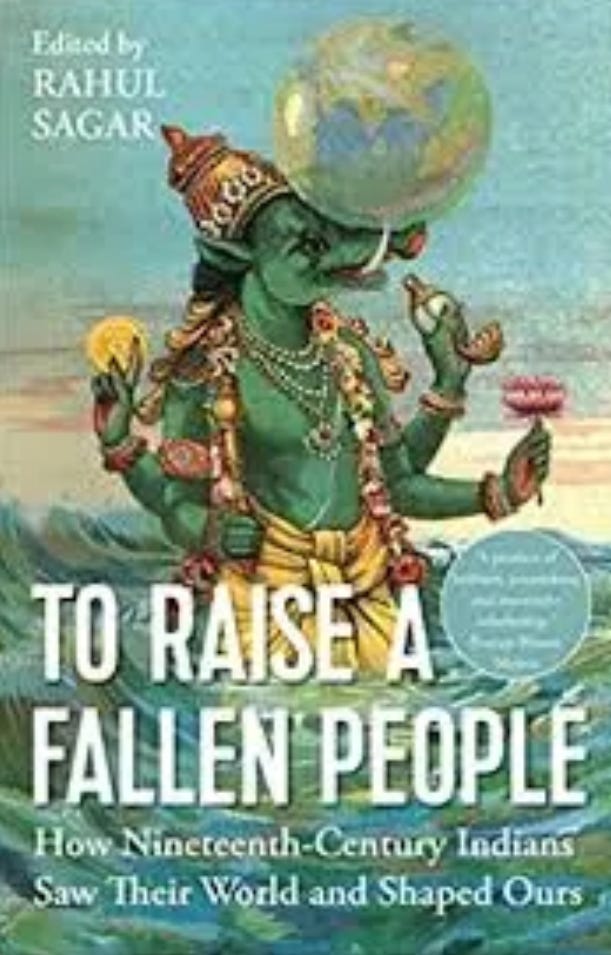

To Raise A Fallen People, edited by Rahul Sagar