Deconstructing ‘Chainsaw Man’ from a Traditionalist Paradigm

A Hindu Traditionalist View of the Themes of 'Chainsaw Man'.

Stories are myths and myths encode symbols - and symbols determine meaning. Hence it becomes necessary to examine the stories around us in order to ensure that we can discern noble symbols from fallen ones. One such popular story we find around us in the anime format, is ‘Chainsaw Man’.

‘Chainsaw Man’ is a popular dystopian action anime (it has a single season as of May 2025) - a Japanese animated series; based on the manga of the same name by mangaka Tatsuki Fujimoto.

In this essay, we shall comment on the main character and his context within religious and materialist frameworks, the conception of Devils in the story, and then deal with four other important characters in the narrative in view of their symbolical worth; and then present our final verdict.

Let us first have a look at a brief outline of the story.

Introduction

The story takes place in an apocalyptic setting where the world is infested with ‘Devils’ - grotesque and powerful fantastical creatures who are generally harmful to humans; and create havoc and death in their wake. To counteract this Devil threat, the world (and particularly Japan) is “protected” by a centralized bureaucratic organization which is dedicated to eliminating these devils - the organization is called the 'Department of Public Safety’.

Our protagonist here is a young man named Denji, who grew poor and impoverished. Denji becomes attached to a pet devil, the ‘Chainsaw Devil’. He nicknames it ‘Pochita’. In a series of circumstances which would have otherwise caused Denji’s definite demise, Pochita fuses itself with Denji in order to resurrect its master - and so Denji now becomes a ‘Devilman’: a combined existence of a human and a Devil - the Chainsaw Man. Eventually, he is recruited by the Department of Public Safety - and the rest of the story is about his adventures with the other members of the organization, and further world-building of this fictional universe.

Denji’s Materialism and the Role of Religion

First of all, we may notice Denji’s socioeconomic condition - it’s quite bad. He’s poor, uninformed, naive, and materialistic. To examine this further, we might first observe it through a Marxist lens, and then we shall notice the severe limitations of that lens.

The Marxist thesis says that politico-cultural superstructure sits on top of the socio-economic base - that a person's economic condition determines his culture. In this way, Marx referred to religion as the opium of the people - as a sedative which numbs suffering and keeps man from rebelling against economic oppression; and hence it is embraced by the masses.

Keeping this is mind; Denji, for example, as a poor man - should ideally also be somewhat religious. But what we find here, is quite the opposite. As related before, Denji is very materialistic - his goals of life do not go beyond the gratification of the senses. He is as far from religion as is the underworld from heaven.

Marx held that the most fundamental fact is that man has a stomach, and this is the economic foundation of human nature. Denji exemplifies and subverts this - he is a poor man whose mind has no room for religion, and his actions betray the belief that man is nothing beyond the material.

But, well, how likely is it that man with nothing else to hold on to, will hold material desires instead of religion as his utmost goal? Denji is quite explicitly an illustration of this: Pochita resurrects Denji on the promise that Denji would act out and achieve his dream as the price for this new life. What is his dream? To eat good food, sleep well, fondle a girl's breasts. Utter materialism - and no less with a dose of carnal vulgarity.

It is, in fact, possible that a man like Denji holds on to materialist desires inspite of being poor and unfortunate; and the answer comes in two parts.

Firstly, materialist egalitarianism - in the form of the many incarnations of socialism and Marxism, and meterialist individualism - in the form of the many incarnations of liberalism and consumerism - have attempted to anaesthesize the cultural and spiritual sensibility of man. They have tried very zealously to feed it into the minds of the people that man is only concerned with commodities - he either produces commodities (the Homo faber of socialism) or he consumes commodities (the Homo consumens of liberalism). Both of them are reductive, but what Denji exemplifies in the anime is Homo consumens - individualist consumerism. Man as consumer - and nothing much more than that. Humans are susceptible to propaganda, and the masses are more so than the intellectuals. Hence, someone like Denji may find temporary comfort in materialistic prospects in such an ideological environment.

To be fair, a Marxist view would perhaps term this as late-stage capitalism and commodity fetishism — yet it is nevertheless important to not forget that that man in the Marxist imagination is Homo faber — the producing man. If man’s fundamental essence is in his labour, then why is it not in what he consumes? Nothing is produced if nothing needs to be consumed, and nothing can be consumed if nothing is being produced. Both are two sides of the same coin, and united together in reducing complex cultural and spiritual phenomena to materialist caricatures. However, while we may accept that such comfort may be availed of by a man like Denji, it would only be temporary, because meaning is more important in life than consumption - as certain other characters of the series, and later Denji himself , illustrate, as we would examine in later sections of this essay.

Secondly, the world of 'Chainsaw Man' is post-apocalyptic - as said before. Its apocalypse comes in the form of the infestation of 'Devils’. Not only Denji, but no character shows any kind of inclination towards religion. But this is actually not an adequate explanation. Contrary to what some dystopian fiction may suggest, a dystopia would not make religion extinct - but would actually make the conditions even more suitable for its rise. The grandest of divine miracles happen when humanity is at the brink of collapse - as Hinduism affirms the doctrine of the coming of avataras, which occurs at highest points of tyranny of adharma. Religion can never disappear or go extinct no matter how much consumerism or vice accumulates — even though it might lose a bit of its influence in society because of the decadent tide of the Kali Yuga — because man is not just an emotional and physical, but also a spiritual being. And especially in times of crisis, when reason fails, sentimentality fails — then religion alone rescues man both mentally and physically from his predicament.

Hence, we must diagnose the absence of religion in the world of Chainsaw Man' as necessarily a flaw of much of modern fiction which attempts to create secularized images of meaning in a world that is slowly being deprived of religious vitality - through the relentless march of the Kali Yuga. This religious vitality isn’t merely an 'opium’, as Marxist framing may make one think. Religion provides meaning, contentment, stability, and most importantly a metaphysical and transcendental anchoring point to the individual. The opium is necessary for a complete and holistic human experience, and it is a sedative exactly for this reason - because it contains the human propensity for violence and conflict - it provides space for harmony and solidarity rather than rebellion and chaos.

The 'Devils' - Nihilistic Jungian Shells

Before moving further with the analysis of Denji, our protagonist, we might have a more detailed look at ‘Devils’ in the ‘Chainsaw Man’ universe. These beings seem so central to the story’s narrative, so what indeed are they?

‘Devils’ are, according to the anime lore, physical manifestations of the emotion of fear - collectively present in human beings. Humans fear zombies, so there is a zombie devil. Humans fear swords, so there is a sword devil. Humans fear guns, so there exists a gun devil. And, humans fear chainsaws - and that is why the chainsaw devil exists.

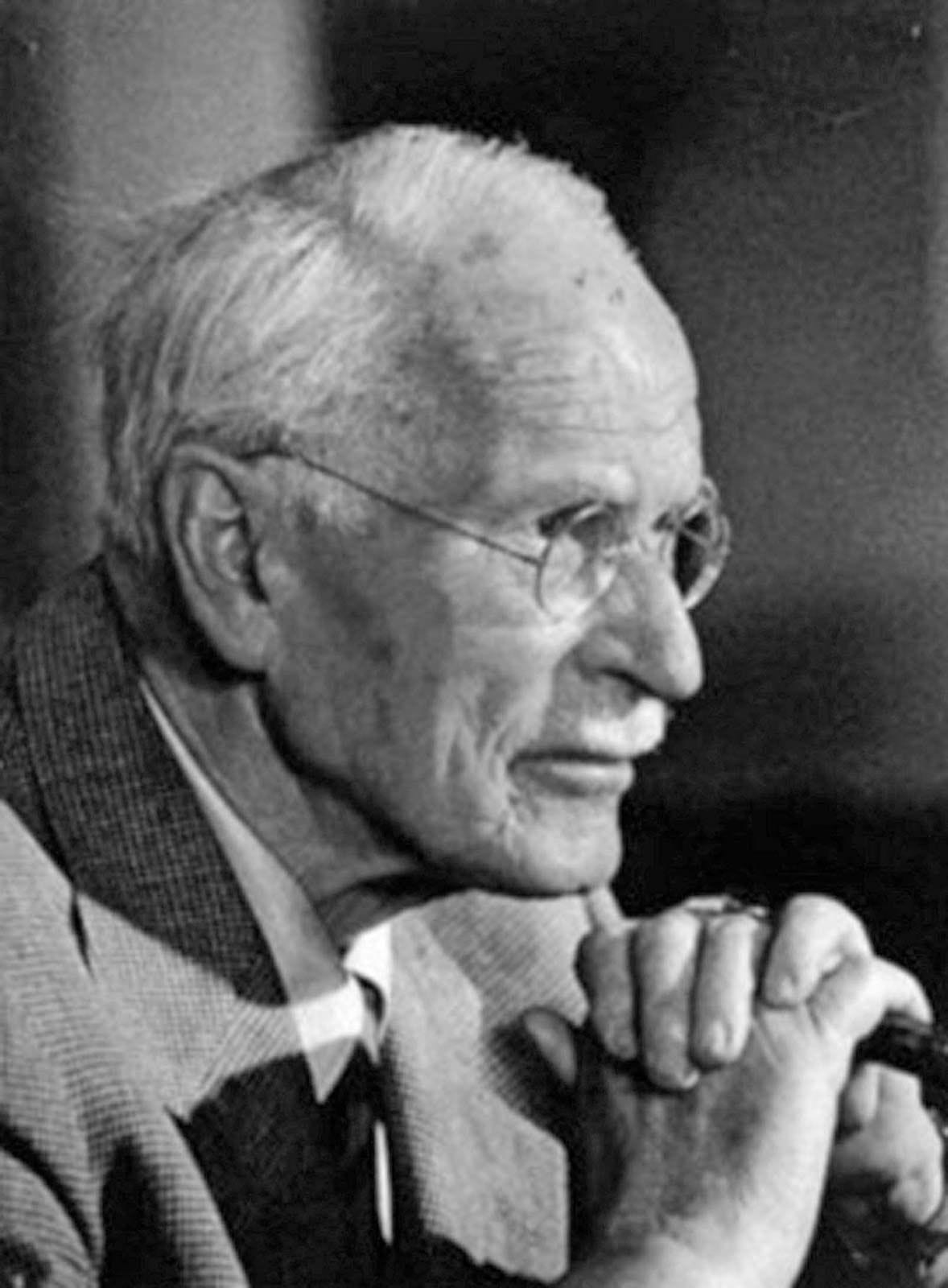

To better understand what this means, we might lean on the concept of the collective unconscious - theorized by the psychoanalytical psychologist Carl Jung. Jung believed, like his teacher Sigmund Freud, that much of human behaviour and psyche is explained not merely by what we do or understand consciously, but by what lies inside the mind’s unconscious. But unlike Freud, Jung’s conceptualization of the unconscious was far grander. He believed that the unconscious is not merely personal, but also collective. The collective unconscious consists of the shared psychic energy of all of humanity - mainly our ancestral memory preserved in an evolutionary manner. Jung identified a number of archetypes within the collective unconscious, and one of them was the shadow - that dark aspects of it which we strive to suppress.

What the story says - is that devils are physical manifestations of multiple myriad aspects of the collective unconscious - but even among them, only of those aspects which are feared. More akin to the concept of the shadow.

Now, this situates the fantasy of the anime on a firmly anthropocentric ground. Devils are not explainable by science - they’re magical creatures. What governs their existence is not reason, but emotion. Rationalism is rejected, and irrationalism is embraced. The question is: how correct is this a view of reality? Is reason more important, or emotion? Or a third thing?

The answer lies in understanding the limitations of the Jungian collective unconscious, which would automatically bring in view the poverty of the anime’s conception in its stark nakedness.

Jung, as a psychologist who rightly rejected the tyranny of rationalism and scientism, did however cage himself within emotions and symbols. His explanation of religion is similarly reductive - that religion is simply a respository of parts of the collective unconscious. To the contrary, religion, as has been affirmed by most faiths, is neither reducible to reason nor to emotion. The root of religion lies in something far beyond the human mind. It lies in the Absolute, the Transcendent - what we call Brahman in a few branches of Hindu philosophy — something that is ontologically and existentially separate from what is merely mental or physical.

This is how we must understand the validity of the concept of Devils in the ‘Chainsaw Man’ anime. They are ontologically not beyond humanity, they are merely materialized fears. They are not truly devils, but counterparts in flesh of what humanity is psychologically terrorized of. It’s a fantasy of the inferior variety - a human-centric fantasy which only incompletely accounts for holistic existence.

Denji’s Lack of Idealism with Potential for Growth

Coming back to Denji’s character - Denji is not wholly the Homo consumens he was outlined in this essay earlier - there is some more nuance. He fulfills some of his dreams in his life at the Public Safety HQ - he eats good food and fondles a woman’s breasts. And he realizes that these pleasures - if they can be called so - are very empty. There is nothing magical about these things - our body experiences them once and then soon forgets about it. And in this manner, Denji grows - even if only a little. This must be highlighted, however, that Denji is the most nihilistic character in the story despite being the protagonist. We miss in him any sort of a dignified idealism which makes men great - neither do we find in him sustained discipline or chivalry. Denji fights, Denji struggles, Denji wins, and he does have a few genuinely tender and compassionate moments - but the lack of striving for higher meaning is too conspicuous to be left unnoticed. He is a man, but not a masculine man who acts as the guardian of religion and family, as someone who honours and protects women; he is, to be blunt - a brute, who is enmeshed in the swamp of modernity.

Now, we shall move on to the other important characters.

Aki - Noble Knight in a Hostile World

Aki Hayakawa is a veteran competent member of the Public Safety organization, and he is driven by the desire to exact vengeance on a certain devil (the Gun Devil) for killing his family - and that is his ideal. In many ways, Aki is the very antithesis of Denji - a man who stands for something higher than mere sensual bliss. While revenge can be seen as violent, when one desires revenge for a cruel harm to his loved ones - then that desire emerges not from hatred but from love. In fact, it comes from a feeling of responsibility and protectiveness for what one sees as his community - and is a very honourable sentiment in this sense. Aki is disciplined, elegant, serious, and civil - traits which symbolize personal self-regulation and high discipline. He is the true hero of the story as far as moral height is considered as any measure of importance.

Next, we would analyse the female characters of the series - and this we shall look at primarily through three very distinct ladies in the story - Himeno, Power, and Makima.

Himeno - Honourable Lover with Caveats

Like Aki, Himeno is a competent veteran of the Public Safety Department. She conducts herself in a very loving, compassionate, gentle - yet committed - manner; and in that sense, Himeno is deeply feminine. She is, unlike Aki, not reserved; but very informal, jovial and even mischievous in tone and temperament - and while that is not wholly proper, it is yet deeply human. However, her actions sometimes do slip into vulgarity - consequently of her sometimes overly mischievous and informal nature. This degenerates femininity into an ulterior and debased form - when the woman transforms from the mother, queen, wife, or sister; into a harlot or an animal. But on the whole, Himeno is indeed appreciable for her femininity, and also for her idealism. She has intense love for and devotion to Aki - who is her partner in work - and this great devotion culminates in a tragic yet deeply ennobling self-sacrifice; she lets herself die in an ultimate attempt to save her lover’s life during a dangerously vulnerable moment in battle. While her status as a fighter might not be reflective of traditional femininity, in times of crisis, the woman has full capability of displaying strength and of protecting what she cares for. Just as Aki provides us gilmpses of the heroic masculine man in that dystopian world - Himeno complements that symbolism with her feminine counterpart to Aki’s masculine nature.

Power - Grotesque Caricature of the Feminine

Power is Denji’s partner in work - and unlike the other characters analysed here, Power is explicitly non-human - she is described as a ‘Fiend’ or ‘Demon’ - depending upon the particular translation used for the Japanese original. This creature is a Devil which has taken over a human corpse as a desperate effort to survive. This is a very grim idea inherently, but the anime does not treat this grim idea right here with the kind of seriousness which it deserves. Regardless, Power is, therefore, a Devil - and she only looks human - thus her looks are deeply deceiving. When we observe her character, we find her as Denji’s female counterpart in many ways, just as Himeno is Aki’s female counterpart - though in certain aspects, Power is even more raw and wild than Denji. She is the complete antithesis of virtue - though as is the convention in storytelling, she is depicted as a naturally beautiful and attractive female since she is one of the main characters; but apart from that, we find almost nothing else - except brief glimpses of compassion at rare moments, just as in Denji. Power possesses no self-regulation - she has no hygiene, no emotional attachment to anyone else (except her cat, a single relevant exception), no sense of modesty, and is possessed by sadism and the will to destroy. To the unsuspecting viewer, Power might appear as endearing because all these vices of hers are mainly presented in the anime as moments of comic relief. But behind the laughs, there exists a nature that is wholly degraded and deeply unfeminine - and of course not even masculine. Power is an example of an aestheticized but corrosive ugliness, masquarading as harmless innocence.

Makima - Tyrannical Seductress with Elegance

Finally, we come to Makima. She is the most imposing and enigmatic figure of the story, and she heads the Department of Public Safety. As far as her conduct is concerned, it is to be admitted that she is exceptionally disciplined and self-regulated. However, not all discipline is necessarily good in an absolute sense - because discipline can also be instrumentalized for ends which are malicious, depraved or tyrannizing. And this concern is what has partly been depicted through Makima - though her intentions are mysterious, it is strongly hinted that they are not noble. True discipline is what contributes to the upholding of the divine order and which harmonizes human existence with itself and with the divine; that discipline Makima lacks. While she plays the role of the queen of her kingdom - the Public Safety Department - in an able manner, she also acts as a seductress when necessary; she is essentially a competent manipulator. The seductress is feminine in the sense that she weaponizes her sexuality; but deeply unfeminine in the sense that by doing so, she debases it rather than honouring it. We may note that it is only a society with deep vulgarity - where the carnal desire is held in the highest worth - which works as the most perfect ground for a seductress to operate in. The world of ‘Chainsaw Man’ is deeply materialistic in many senses, and so is Denji - who falls under Makima’s wily seduction in the story. However, we find that Makima’s discipline - even if instrumentalized for unworthy ends - gives her a certain air of refined elegance. That elegance positions her decidedly within the mould of the lady, as opposed to the mere woman. Her cultured mannerisms are admirable and even inspiring - even if they may be performative. Makima is far more flawed on a fundamental level than Himeno, but she is much superior to what Power represents. She has authority, strength, and the necessary cruelty which is demanded of a hard taskmaster who heads a bureaucratic apparatus that deals with paranormal violence - and she has the guiles to almost hypnotize her subordinates under her sway, and both Aki and Denji see her and pursue her (in varying degrees) as a romantically desirable woman. But as noted before, these very guiles contaminate her femininity and desacralize its essence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this verdict must be given to ‘Chainsaw Man’: it is deeply reflective of the modern decay in contemporary culture - yet it preserves glimpses of what honour can look like when it surfaces among the little specks of sunlight through the depraved modern forest canopy.

PS: Interested Indian readers, who understand Hindi, might consider watching the show in its Hindi dubbed version - it has been voice-acted very competently, and the language used is not excessively full of English and Persian-Arabic vocabulary, unlike many other Hindi dubs of foreign media content in current times.

It's quite good but your premise for morality and vulgarity seems Christianity based to me. Keep it up.🙏

😳